Is it truly possible to subvert in neoliberal* academia?

What shows up when we look with discernment

In my last episode of the fractured memoir from a few weeks ago, I neglected to share an important detail about the area surrounding Blue Mountain Center in the Adirondacks of New York State. This detail became evident during my visits there, but somehow, in my recent reflections this information became invisible. I share this now as a reminder to myself and to you, dear reader, to always look more carefully under the surface, especially when you are seduced by the beauty of a place.

Soon after arriving at BMC, I learned that the lake was dead due to acid rain, and that much of the Adirondacks, and vast swathes of natural landscape east of the formerly industrial Midwest were moribund. The ecocidal reality of having damaged so many parts of our home planet through the immense greed of capitalism and industrialization could be sensed at BMC through the sobering daily silence on the lake. It was a peacefulness that was not really comforting. Still, I was hypnotized by the beauty of the trees and the ability to walk unaccompanied through the woods for hours. In order not to be in despair, 24/7, most of us prefer to smell the pretty flowers rather than inhale the stench from the local pulp mill. Living with these kinds of contradictions is part of what compelled me to devote my life to looking at cognitive dissonances, creating art and writing about them. It’s also what motivated my interest in subverting the status quo as an educator, so that others could share the paradoxes they’re experiencing through their art making and raise consciousness. It has seemed that the only way to stay sane was to inspire cohorts to help change things.

Now, in my post-academia chapter, when I am slowly preparing to start teaching as an independent in 2024 (with sessions in my studio and in virtual space), I’m looking more closely at what subversion really means: who’s really threatened by it, and who is aided by this approach.

Inspiring this revisionist look at a career that was led by “teaching art as a subversive activity” are multiple factors. One is the price I paid for doing such, and why I felt compelled to make my life as an artist even more difficult by complicating it in this way. The other provocation for reviewing this intention is something I mentioned in my earlier book, Arts for Change: Teaching Outside the Frame (New Village Press) on page 6. While in graduate school, I read an essay by the ethnopsychiatrist, George Devereux. He reported on a conversation between Cardinal Mazarin who advised King Louis XIII of France (in the mid-1600s). They were in the palace and heard a wandering minstrel singing about the rising taxes; he was complaining bitterly about the corruption of the church and the monarchy. The king asked Mazarin if they should jail the singer, but the Cardinal responded with a smile: “if they sing, they will pay.” Devereux used this story as an example of how art, particularly political art, can be a “harmless safety valve.”

Since I wrote the book, Arts for Change, 15 years ago, my attitude about what will change the status quo has been shifted by many encounters, both internal ones and things I’ve witnessed. I see more clearly that our actions can be like the wind created by the wings of a peregrine falcon; so many ripple effects that are hard to measure and assess. There’s so much that we can’t see that has an impact, and that is what interests me now - what’s happening in the dark, in the soil, in the margins, and in other realms.

As we continue to ask questions, be curious, listen, and create bridges rather than contract and become rigid out of fear or anxiety, we discover that change percolates in so many unexpected ways. If it’s just steam escaping from the pressure cooker, so be it, but steam can gather to become a cloud and then a storm that moves something that seems immovable. Nearly 40 years ago, my own steam began to dislodge my cynicism (a recipe for inaction), and with it, my earnestness to retool studio arts curriculum to be more socially engaged. This was not very common at the time, and as a result, I was considered subversive.

Sometimes I would be invited in as a guest artist or speaker because I was considered to be an exciting flavor of something different, but that something would not be invited to stay much longer than necessary.

In 1984, I arrived at the Carleton College campus, a landscape that I thought I knew well from my four years there in the early ‘70s, but I found it changed in many disturbing ways, some of them mirroring the sad changes brought in by the Reagan era. The most painful thing about this was that the current students seemed to know nothing about the recent histories that had been erased; that seemed like the most cruel piece to me.

There was no longer a vegetarian cafeteria where 4-student teams cooked for 250 others in the community, buying our own supplies (with the same generous budget as the meat-eaters), sometimes getting our produce from another student project (The Farm), developing recipes together, and collaborating in a playful and productive way. Only a decade after that student-run initiative, the corporate food service had coopted this innovation and was offering a veggie entrée (and not a particularly healthy option), and students were ignorant that their food had ever been prepared and served in any other way.

There were no longer late night debates in the Tea Room where for many students the deepest education occurred. Instead, students were being intensely bookish in the library, researching their papers, studying for exams, competing for the best grades, double majoring, and researching the prestigious grad programs, so that they could compete for the professional degrees that they had been preparing for. It felt more like a factory of learning rather than the hot bed of counter-culture, a place where you could meet the folks with whom you could live on a commune or organize a grass roots movement that I remembered from my youth. Reaganomics had prevailed. Students were either aware consciously or unconsciously that the social safety net had been frayed, and they were pragmatically assenting to some of the rules of capitalism - compete and don’t look at the woes of others or if you do, just give to charities. In other words, be a good liberal, but don’t rock the boat.

To be fair, there were many students preparing for lives of service as doctors, lawyers, professors, as well as work in the non-profit sector, and in local or global politics, but I didn’t notice the complete rejection of 9-5 life and from capitalist values that felt commonplace in the early 70s. There was some activism happening, but it seemed a bit more carefully manicured, like the tent city on the quad to protest apartheid and the Democratic Socialists organizing in the dorms for the annual meeting.

There were still wonderful teachers on campus who I want to lift up because they did such great work; every one of them is now an ancestor. They included the beloved Paul Wellstone who had not yet moved on to the Senate, the brilliant feminist thinker, Maria Lugones, the marvelous scholar of all things Indian and a great chef of that cuisine, Eleanor Zelliot, and the art historian, Lauren Soth, who opened the door for me to teach there. He was the one who followed my NY career and offered me the brass ring that allowed me to move on to my next chapter.

When I arrived on campus, I was treated kindly. Eleanor gifted me with a huge collection of Ben Shahn books - I was amazed, since Ben Shahn’s writings had inspired me as a sophomore to become a teacher (seeing that role as “more than” rather than “less than” in his book, The Shape of Content). At the same time, I was handed the traditional curriculum of the painting professor who had traded places with me. I had to figure out how to make these classes more resonant with my desire to expand the students’ worldview about art and what it could give them and how sharing their stories could be of service to others. I decided to give the students visual problems to solve that included building a still life as an altar to an ancestor, animal, or tree, or creating imagery derived from symbols found in a recent dream or meditation. They could still learn visual grammar and expand their tool kit for making compositions by working in this way. As they sat down to draw, there were always ecological and labor issues that could be discussed that they may have not considered, like where did their paper and pencils come from, who made them and in what working conditions, and what resources were used to make them.

Retooling the color theory course was especially interesting since I had found the previous curriculum’s focus on Joseph Albers’ formal & perceptual approach to color insufficient. I wanted to experiment with how this topic could generate interdisciplinary understandings of color, and that, of course, took me to the psychology of color and how it’s used to manipulate, market, and soothe, the sociology of color and what that says about skin privilege and race, the history of color and how it could signal violence, tension, and competition, the joys and varieties of color in nature and how that relates to nutrition and interspecies communication, and ways to envision spirituality often found in color via chakras, auras, and the insights found in Concerning the Spiritual in Art by Wassily Kandinsky.

In an open topic course, I was able to dive full tilt into art as a tool for social engagement. After sharing an overview of the field, we did a bunch of brainstorming to find out what issues were rising up among the students. Given that this course happened almost 40 years ago, in the era of pre-digital documentation, I can only recall that we did a moveable mural that depicted students confronting the injustices of the time; if I have an old slide of that piece, I have no idea where it is. I recall that students created public pieces on campus to raise questions about power and hegemony, and a series of satirical t-shirts were made that said “NAIDUS MADE US.” The latter project, while humorous, made me pause; was I really helping the students question things, or was I being coercive?

The idea of proselytizing made me shudder. The last thing I wanted to do was convert students to a particular ideological point of view, but I did want them to develop their critical thinking and have access to more resources that would improve the latter - and obviously for some, these pedagogical impulses are ideological in an anti-fascist sort of way. Fortunately, at Carleton, I was given carte blanche to run with those impulses. But in subsequent academic positions, I ran into conservative colleagues and administrators who felt that the questions I was encouraging students to ask and the fact that I was empowering them to find their unique voices and tell their own stories, was dangerous. I will share some of those instances in future episodes.

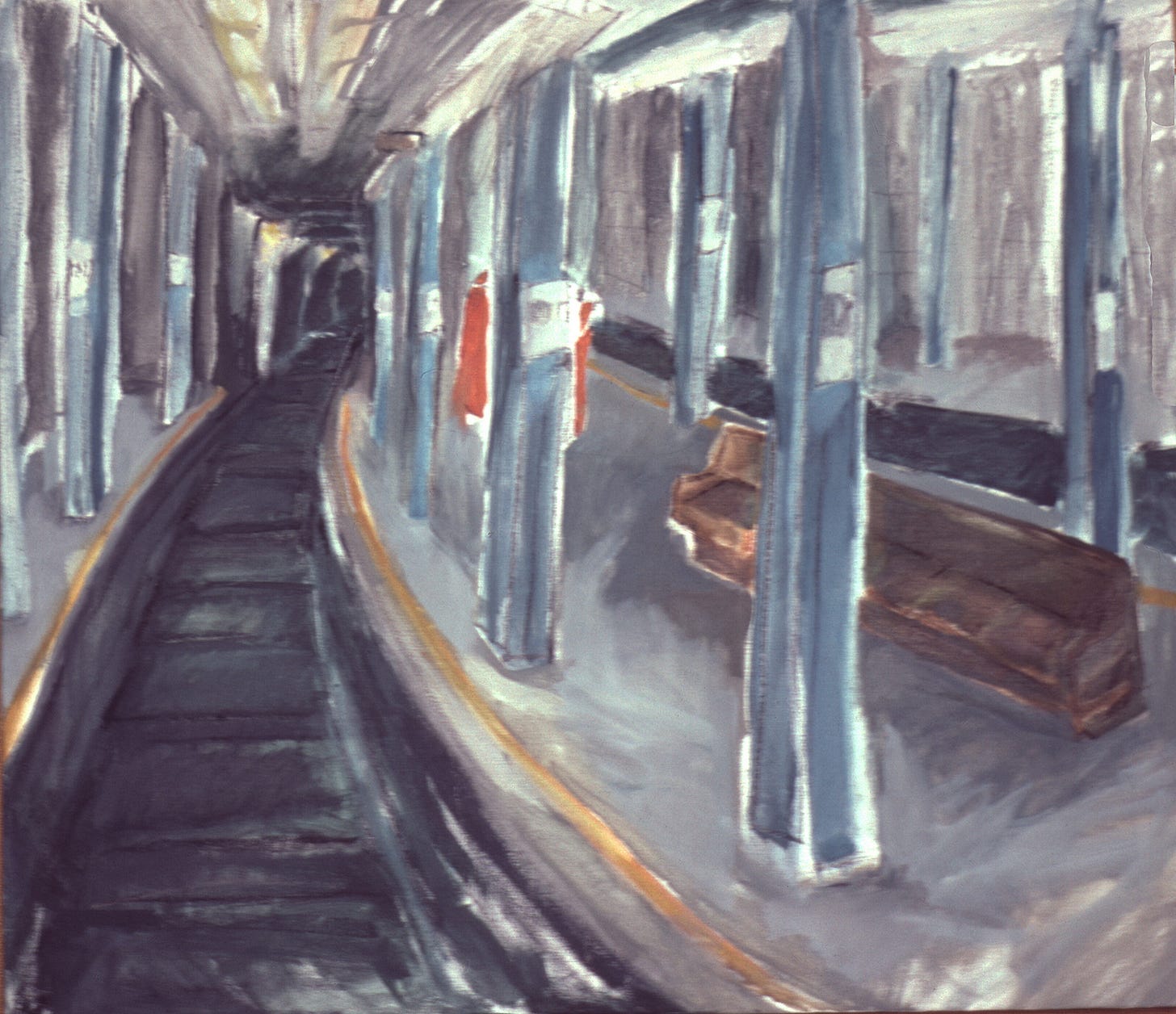

While I taught at Carleton, I needed to make art to process the huge transition I was going through. It’s no surprise that I started painting memories of Brooklyn and NY life. Over time, my subject matter shifted, and I was able to look at the crisis in the farming communities due to the agribiz buy out of lands, the ensuing foreclosures, suicides, etc. and how that trauma was rippling out locally. In the Twin Cities, I saw the beginnings of gentrification via the invasion of artists, boutiques, and restaurants moving into formerly industrial areas, and the ripple effect of those precursors to rising rents.

The Subway, Oil on canvas, 4’x5’, 1985

The Subway Station, Oil on canvas, 4’x5’, 1985

The Brooklyn Loft, Oil on canvas, 40”x56”, 1985

“Farm Foreclosure,” Oil on canvas, 4’x5’, 1985

After almost two academic years at Carleton, enjoying the students, the perks of a college with generous funding for artists to travel, free housing, and my first academic salary with health benefits, I was not feeling the survival stresses of my previous chapter. The edge of daily life was smoother and the anxiety that had fueled some of my previous activist work was diminished. So, of course, I was being teased for being a “sell out” by the art historian who offered me the gig. As much as I appreciated the privileges listed above, I needed to better understand how to navigate this new terrain with my anti-establishment hat on. I didn’t have a strong cohort on a similar path with whom I could question the merits of subverting within the system, but I was feeling the rewards of seeing students question things that they had taken for granted and seeing them stretch into more parts of their stories. Was that enough?

Now I can look back and see that my presence on campus and the questions I brought to my classes had an unexpected positive impact on someone besides my students. My first year on campus, I lived in an old house that had been converted into two apartments. The other apartment housed my younger colleague, Fred Hagstrom, who taught printmaking and was brand new to campus. Fred was a devoted teacher and deep thinker. His edgy and emotionally expressive work was not socially engaged at the time, but we had lots of discussions about the politics of art as well as social issues that were provoking us at the time. I didn’t realize that our conversations planted seeds, but years later, he sent me some of his artist’s books that had social themes, and when I came back to campus as comps advisor six years later, I saw that many of his students had created senior projects that were socially engaged. His introduction to my campus talk floored me when he said how big an influence I’d had on him as an artist and teacher. So we never really know how, where, and when our offerings will yield results, but it’s a delight when they do.

During my time at Carleton, I was given a budget to bring in visiting speakers because my colleagues wanted to take advantage of the networks I’d accumulated during my years in NYC. I was really thrilled to be able to bring such intriguing, dynamic, and brilliant folks to campus: Lucy R. Lippard, Suzi Gablik, Martha Rosler, Jacki Apple, Martha Wilson, Hans Haacke, Jon Pounds, Ricardo Levins Morales, Suzanne Lacy, and others that I sadly can no longer remember. Suzanne’s work made such an impression on the faculty that she was invited to take my place when I left, and due to her new location in Minnesota, she was able to develop the very impressive community art piece featuring elder women called The Crystal Quilt in the Twin Cities; just another example of subverting the status quo by lifting up the work of others on the path.

In 1985, I was invited to attend a conference of the Alliance for Cultural Democracy in Chicago, and met up with an exciting crew of artists and performers who were working outside of academia. A handful of them came from my activist artist cohort in NYC (PAD/D, Colab, Group Material, and Carnival Knowledge), but most were unknown to me, and came from all over the continent (as well as the UK). It was amazing to discover this treasure trove of socially engaged cultural activists & scholars (remember that this was the pre-internet days and finding each other required the funding and mobility to attend gatherings). Many of these folks expanded my world view and made me rethink my own creative practices. I was introduced to the concept of “cultural democracy” for the first time, as well as the modern conception of the griot. I witnessed how storytelling was an essential piece of empowering communities to see themselves in each other and to voice concerns about the status quo. It was incredibly reassuring to know that this movement existed. I took notes and read as much as I could to bolster my understanding and confidence, and went back to teach with a much larger cache of resources.

At some point, during my second year as a Dayton-Hudson Visiting Artist, I was invited to apply for the tenure-track position that had been vacated. The colleague whom I had replaced was not coming back. I applied with some trepidation. I was not thrilled about being land-locked (despite the sculpture professor’s description of the wheat fields appearing like the waves of the ocean) in such a white, middle class environment. After living in a spectrum of color in NYC, I was uncomfortable in this midwestern college-town, and thankfully, my colleagues made it easy for me to leave.

A few weeks after I submitted my application for the job, two senior colleagues invited me into their office. They shared that they had been deeply appreciative of what I had been doing with students and that my presence had been an “injection” of energy that the program had desperately needed, but they were looking for someone more traditional to sit in that tenure-track spot. An “injection”…. that term returned to haunt me a few times over my years in academia; you will learn why in my future posts.

Many months later, when I learned that the art department ended up hiring a white, straight man, I was deeply discouraged, even without knowing anything about him or his work. Still, over the years, the program has shifted in some positive ways. The studio art faculty is now half female, although it seems that artists of color are either not able to tolerate living in such a white community or they are only hired for visiting positions. The art historian, Lauren Soth, who reached out to me initially, met up with me at art conferences, and shared that his survey classes were now filled with the art of women and people of color. That’s not a small thing given that I had seen maybe two women artists and maybe one artist of color in his survey class as a freshwoman.

I had applications for tenure-track positions submitted elsewhere (Hampshire College and Cal State Long Beach) so I understood that the door shutting at my alma mater might not be the end of my academic career. I became one of the top three finalists for both positions. At Hampshire, I almost had the job until they found out that I wasn’t the Person of Color that they imagined me to be. At my last dinner on campus, a faculty member made a joke with a Yiddish punchline - he was of Jewish heritage. I laughed at the joke. The other faculty members looked at me startled and I was taken aside by this same person who made the joke. He said, “are you Jewish?” and I replied, “not a practicing Jew, but it is my cultural heritage.” He responded by saying, “we assumed that your ancestry came from India based on your name and appearance. This is a targeted position for a person of color. We already have too many Jews on the faculty here.” I was astonished, but it was long before rules about saying such things would get search committees into trouble.

My application at Cal State Long Beach was successful. They wanted an experimental artist who had been recognized in NYC art world. I was invited to join the Drawing & Painting program which seemed to be divided between the formalism of abstract expressionism and 19th Century academic and figurative painting. I was the second female hired in that program. The first female seemed very insecure and was clearly struggling with many issues, and everyone else was a white man. Little did I know that just asking questions, whether they were about the concepts informing an art work or about the values of the art world, would get me into trouble there. As much as I loved working with the diverse students attending this public university, I had entered a battlefield for which I had not done any basic training (sorry for the military metaphor here, but I don’t know how else to describe it).

And with that foreshadowing (yes, Chris, another cliff hanger), I will starting working on my next episode in which I will dive deeper into how neoliberalism as well as other oppressive systems manifested as I continued on this journey through academia.

*Thanks to Doug Paterson for historically framing the term, “neoliberal.” “It comes from post-civil war corporate assaults on "public" government that created an economy that would not only stop regulating the Corporate State (the real US government) but would instead help it to make profits. They called this "liberalism" in c. 1880 - 1890, and it lasted until 1929 when "liberals" like FDR gave the public government renewed power over the Corporate State. This lasted until perhaps 1980 and Reagan, though "neo" liberalism (of the 1980's variety) was already rising on steroids. Telling this story is a teeny tiny subversion maybe, and it can be fun, even a prep on the real enemy.”

I feel that many women joining faculty could do with basic training in how to deal with the entrenched patriarchy.

Thanks for these essays. They are fascinating.

Lovely read and beautiful , evocative art. One thing is for sure, I can attest, the more successful our subversion the more true this is..."I was considered an exciting flavor of something different, but that something that would not be invited to stay much longer than necessary."