Blue Mountain Center and Beyond

Finding another path through what was a less complicated woods

After witnessing how long one of the last episodes of my fractured memoir was simmering on the stove, I tried my best to make this one flow with more ease, but fate and physics had other plans. Gravity conspired to topple the just-washed blade of a food processor out of my hand and onto my foot, which was, as one might expect, a bloody mess that direct pressure could not remedy. That led to a trip to the ER and four stitches. I was not “humming” due to the gravity (as the title of this Substack series might suggest). Thanks to my lovely neighbor friend, Lauren, I had good company in the ER and the staff, despite long waits, took good care of me. With mobility being impaired for over two weeks now, one would think that this situation has kept me glued to my chair to write, but the garden and domestic chores still need to get done, albeit slowly.

In the midst of this, I decided to let this “chapter” about the events that led to my departure from the NYC art world in the mid-’80s cook for a bit longer, and drifted into a post that deals more directly with the main thesis of this book: how combining spiritual practices, creative work, and activism in community are the best preparation for navigating the various forms of suffering in this time. With the beginning of those thoughts published, a more expansive discussion of that topic seems to need more time to ferment, so here I am diving back into this episode of the fractured memoir. If you’ve forgotten where we left off, just scroll up to the link in the first line of this post.

In the spring of 1982, one of the women artists in “Not Funny Enough,” Anne Pitrone, had just started working full-time in a toy design firm, so she asked me to take her place at a convocation of activist artists happening at the Blue Mountain Center (BMC) in the Adirondack Mountains of New York. I was excited to go for two main reasons: I hadn’t been out of the city for awhile and I wanted to meet more folks doing activist art. This was part of my quest to find peers who were envisioning and baking healthier “pies.”

The tree outside my window at Blue Mountain Center, Sept 1983, watercolor and w/c crayon, 14x20

At this gathering, I met my brilliant friend, Charles Frederick. Despite a short hiatus caused by my departure from NYC and the impact of AIDS on his life and work, he has remained a faithful friend and mentor through thick and thin, since that time. Charles is one of the most erudite radicals I’ve ever met; his life story about moving out of generational poverty and violence to become an activist/student (Columbia U SDS member), editor, poet, griot, and community art facilitator was and is deeply compelling. After meeting him at BMC, he went on to write a master’s thesis about Black cultural resistance through gospel music, and continues to write and publish amazing poetry, manifestos, and digital photo/text pieces. Our memories of who joined us there over four decades ago include the late Jorge Sanchez Soto, the late Lina Newhouser, the late Jim Murray, the late Seymour Chwast, the late John O’Neal, Ernie Brill, Jan Clausen, Mary McAnally, Mary Bernstein, and others who made our discussions provocative, rich, and inspiring. (Thanks to Ben Strader, the current director of BMC, for searching down in the vault for the 40-year old documentation of that time.) Yes, alas, half of those participants have left their physical bodies; we get old, sick, die, and lose everyone who is dear to us - all that remains are the memories of our actions (as the Buddhist Five Remembrances try to remind us). So may our memories of these passionate activist artists be a blessing (a slightly paraphrased Jewish expression that I only learned in recent years). I encourage the reader to look up the names of these artists to learn more about their legacies. I drew everyone’s portrait at this gathering, but finding them in my archive of images is too labor intensive, so instead I’m sharing one of Charles’ more recent photo/text pieces - you can friend him on FB to see more.

Photo text piece by Charles Frederick 2023

Our convocation was filled with passionate discussions: I had a strong desire to connect with these people who seemed less enmeshed with “making it” in the NYC art scene. In fact, many of them lived far away from NYC and were not interested in the foolishness and desperation caused by being caught in its web. Of course, they were not immune to survival struggles in the hinterlands, and they still had egos, and wanted recognition for their work, but the intentions for their work and the communities that they saw as their audience were quite different from the artists I had been meeting in the city. I saw more clearly through hearing their stories that the ethic of “tikkun olam” (to repair the world) was not uncommon in their creative practices, and it gave me comfort to know that I had peers who shared some of my values and who could teach me a lot.

A few months later, after returning from the convocation, I was invited to participate in the exhibition, The End of the World: Contemporary Visions of the Apocalypse, at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in NYC. Probably a year earlier, I had approached, without any introduction, the curator, Lynn Gumpert. I brought her an envelope that included my resume and a plastic sleeve of my slides of earlier versions of THIS IS NOT A TEST. Ah, the olden days of analog documentation. At that time, the museum lived in the lobby of the New School and was a humble exhibition space. By the time that I received this invitation, they had moved into a much more pristine and formal space. I was thrilled to be invited, but the challenge of representing the dwelling of the last survivor of a nuclear holocaust felt daunting. I needed some time and space to regenerate the project, so I applied to attend an artist residency at Blue Mountain Center (BMC) for a month.

Drawing for the installation of THIS IS NOT A TEST for the catalog of THE END OF THE WORLD: Contemporary Visions of the Apocalypse, Ink on paper, 22x30, 1983

With much excitement, in September 1983, I left Brooklyn for Blue Mountain Lake. It would be my first (and now only) official artist’s retreat. A month earlier, I gave my notice to both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and MoMA. Leaving these teaching artist gigs felt risky, but I knew that I could reboot some freelance income as a graphic design assistant once I returned to the city. Somehow I realized that leaving those museum jobs would be essential if I wanted to move on to the next phase of my life.

When I arrived at the residency, there were many truly delightful things to greet me: the exploding colors of autumn, the smell of cedar paneling lining all the rooms, the luxury of a stately summer estate retooled for community living, beautiful artwork by stellar political artists in each space, lakeside rowboats and canoes to use at our pleasure, scrumptious meals prepared by a very capable cook, and interesting writers to speak with (I was the only visual artist there and my studio was my desk, my journal, my drawing pads, and the great outdoors - a year or two later they built actual studios for artists). My bed was placed under a large drawing of a gorgeous tree by George Grosz. The latter was a big surprise because I knew this German artist as a social satirist, so I had not imagined him engaged in such subject matter. This piece modeled a process that I soon began to imitate: using one’s artistic tools as a way to heal trauma. He had made this drawing soon after leaving a horrific Europe in the throes of WW2; it was clear that he was using nature as subject matter so that he could calm his very disturbed mental health.

The dock at BMC, September 1983, watercolor and pencil, 12 x16

While at BMC, my intention was to rework the installation, THIS IS NOT TEST, the script of the audio track and more, but during the first couple of weeks in this luscious landscape, all I wanted to do was draw and paint trees. I had not spent time in a seemingly “wild” place since age 17 when we bushwhacked into a remote part of the Adirondacks, at the source of the Hudson River, with my then boyfriend (that’s a story for another time). My first weeks at BMC were not providing me with the angst I needed to retool a project about nuclear war. I took solo hikes up trails through the woods and hills, with no fear. I came upon herds of deer, all sorts of plant and mycological life that fascinated me, and looked out at vistas that were filled with riotously-painted mountains in their fall glory and silvery bodies of water. Taking in all of that beauty was so unexpected, pouring so many possibilities into my heart. Why worry about mushroom clouds and a radioactive future….

Until one day, I was relaxing in the middle of the lake, floating on a rowboat, when I heard the deathly roar of jets. They strafed the lake, only 100 yards above my head, and were painted a terrifying black matte. I was dumbfounded by this unexpected assault. I hastily rowed back to shore and walked into the retreat center determined to find out what was going on. A staff person told me that there was a Strategic Air Command base about 20 miles away, and that flight exercises above the center were very typical. So that was scary incident #1.

Illustration of the strafing incident, September 1983, watercolor and pencil, 22x18

Incident #2 happened a few days later when I was awakened in the early morning by an awful shaking and a series of loud booms. I thought I was still dreaming for a moment, and then immediately assumed that the local SAC base had been attacked by nuclear missiles and that we were done for. Such was my tendency towards catastrophic thinking. I walked out to the hallway where my neighbor, a lovely poet from Oklahoma, Mary McAnally, assured me that we had just experienced an earthquake - a phenomena that I had never experienced before then, and something I definitely did not expect in upstate NY. It turned out that the epicenter was in the town of Blue Mountain Lake and that it was felt from Montreal to Queens, NY. I was truly astonished.

The third thing that finally jettisoned the regeneration of THIS IS NOT A TEST was a casual browsing in the BMC library. Libraries have always been a refuge for me when I’ve felt lost, lonely, or confused. On that particular day, I was holding a mixture of all of those emotions, searching for books that might offer me some insight. While pulling a book off a high shelf, the book that was next to it fell down and hit me. After I recovered from being startled, I read the title, “Despair and Personal Power in the Nuclear Age” by Joanna Macy and was incredulous with the synchronicity of this accident. I sat down to read it immediately, and by the next day, had penned a letter to Joanna, eager to connect and find out how to work with her. She wrote back immediately and thus a lifelong relationship began.

The biggest takeaway from reading this book was the discovery of a growing network of folks working with this issue on a deep level. The exercises they were doing in group settings reflected their desire to help people emerge from their numbness, process their grief, and help them generate or regenerate some activist practices. The Fate of the Earth by Jonathan Schell had just been published the year before, and it was clear from his research about nuclear winter that our fearful and emotionally wounded political leaders, as well as the weapons industry and our rabid media fostering the cold war ideology, were dooming every living thing, except for possibly some very hardy bacteria, by allowing nuclear weapons to proliferate.

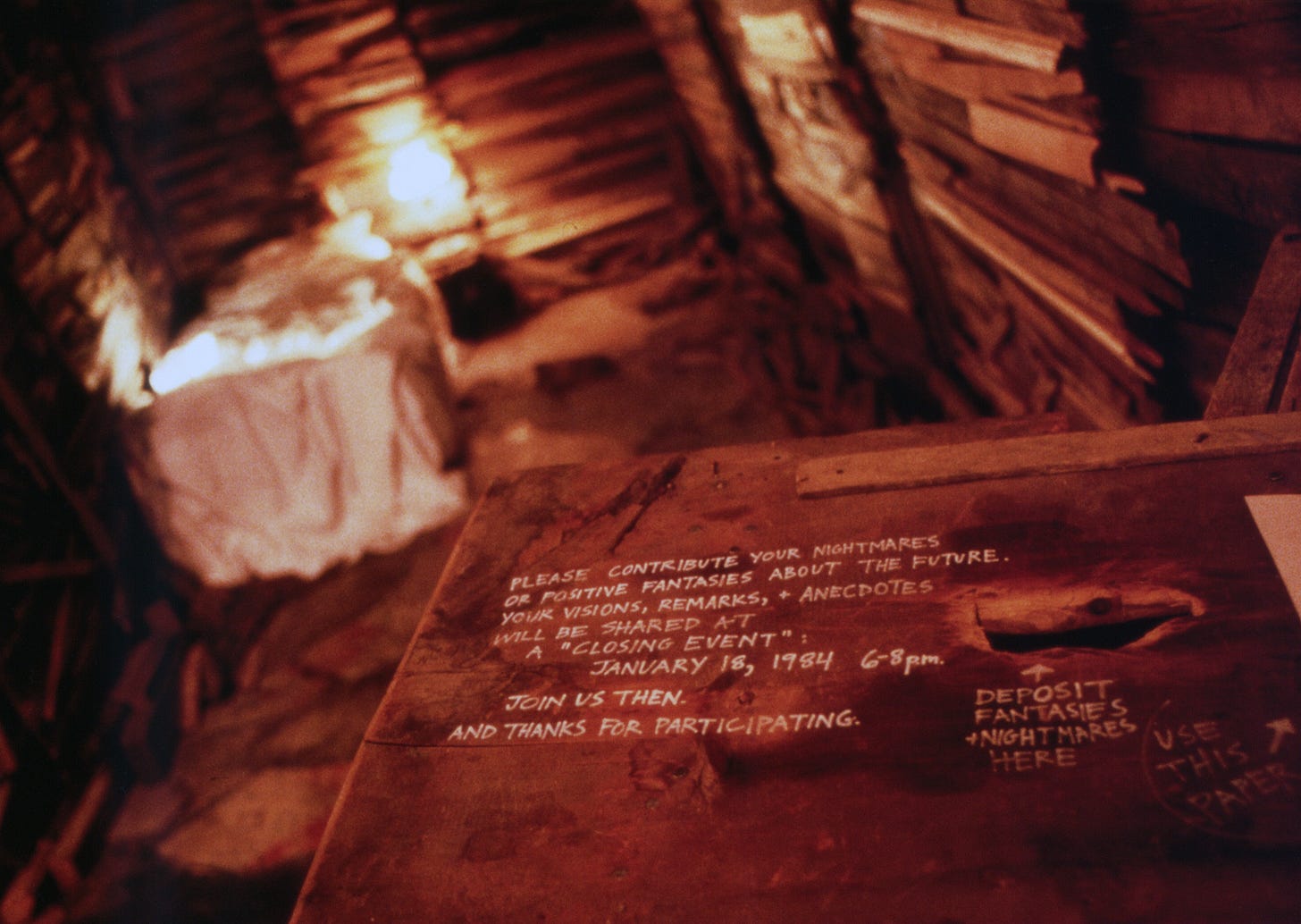

I decided to rewrite my audio text to offer a possibility of a future through taking action (it ended with the line, “we didn’t realize that we had a choice”). I redesigned the installation to make it explicitly audience-participatory (more on that in a bit), and I arranged to get some scavenged wood from someone in Brooklyn who was doing a major renovation. I would spend several months in a dark and dusty basement building panels out of the old wooden slats that would be reassembled in the museum.

I learned through my correspondence with Joanna that some of her peers were leading a workshop in a month and decided to join them. It was an intense experience and I learned a lot from it. As a result, I offered a very modified version of some of the exercises as a ritual for museum visitors who wanted to participate. As I assembled the installation, I built a box with a slot (like a ballot box) where visitors to the museum could leave a hope or fear about the future. As part of the ritual, we broke open the box and invited the circle of guests who arrived that evening to share in the reading of the contributions. Despite the fact that NYC was experiencing a blizzard that evening, over a hundred people (wet, cold, a bit harried from their journeys, and full of anticipation) arrived at the museum to take part in the ritual.

Participants were almost bursting with the need to talk about the issues raised by my installation and the exhibition, in general. They were eager to share their stories of despair and hope. The energy of the crowd and the stories that had been donated to the box were an interesting mix of suppressed panic, edgy cynicism, passionate POVs, classic NY sarcasm, and curiosity. Living under the Reagan regime and the increasingly warm Cold War and the growing anti-nuke movement had catalyzed many. Most of the crowd had seen The Day After, broadcast on a major television station, and were still processing the fear that this film had provoked. Nuclear war had become visible to them and broken through their numbness. Needless to say, the event was extraordinary.

The new audience-participation and ritual aspect of the piece, both terrified and excited me; I knew it might be considered problematic to some folks who prefer the art, its content, and the artist to remain more distant. I was definitely eager to break through that paradigm. Having a dialog with the audience was, in fact, very nourishing, creating a temporary community that many of us need when struggling with certain issues. I recognized that the impulse guiding this work might inspire future projects.

While the art writer, Suzi Gablik loved this piece and wrote about it with great enthusiasm in Art in America and later in The Reenchantment of Art, another critic, Michael Brenson of the NYT, felt differently and shared that this impulse to include the audience was “sophomoric.” Reading his critique, I realized more deeply something that I had begun to suspect before: the NY high art world was going to be a difficult context for me or my work. Attitudes about the artist mystique were crucial to the workings of the art market and the celebrity machine.

There were some feminist and queer performance artists attempting to cut through this artist aura, but most were marginalized. Mary Beth Edelson had successfully created story-sharing boxes in her exhibitions and I found them exciting and thought-provoking, but it would take decades for her work to be taken seriously by the mainstream art world. I could not see Jenny Holzer inviting her audience to offer their own “truisms” as part of an installation or Cindy Sherman suggesting that folks add their selfies of transgressive identities to her exhibit. That sort of dialog between the artist and audience was much more common in the experimental theater world where the impulse to build bridges and foster dialog with communities happened often, but in the visual art world, the paradigm of distant “genius” on a pedestal was paramount.

In the months after the exhibition closed, soon after the reviews started coming in, I sat with a commitment that I had made to myself before leaving the retreat at Blue Mountain Center. The day before I left, on a not-too-chilly fall day, I took my last solo hike. The intimacy I felt surrounded by the forest and its mysteries was so rich that I could not imagine how I would cope with the overstimulation of the city when I returned. I knew that it was time to say good-bye to the struggles and the intensely driven aspect of my NYC life. Several discomforting coincidences on my trip back to the city confirmed this decision, and I took these signs seriously. I started to use wishing dolls (put under my pillow at night) to conjure up the next chapter outside of NYC. Some of my art friends were shocked that I was making this decision, especially given the interest my exhibition had stirred up. One said quite frankly, “if you leave NYC now, your career will fall off the cliff. You are throwing away an opportunity that many of us wish we had.” I recall saying flippantly, “watch me fall.”

I should say now, with the long view of many decades, the determination that informed that choice was not as confident as that last comment sounds. I was extremely ambivalent, or more accurately, my ego was very ambivalent. At that point in time, I had not been sufficiently weaned off the dominant culture’s view of an artist’s success. In fact, there was a huge amount of derision directed at artists who teach. For some, it was a sign of mediocrity. We were assumed to be “less than” because our work was not selling, because we were not selected to be in the Whitney Biennial, because we were not featured in Documenta, nor had we had a solo show at MoMA or won a Guggenheim grant. So much emphasis on winning the solitary chair in that sorry game of musical chairs. And what a load of capitalist hogwash, we ingest daily that supposedly determines our worth. I was sick of it, but was still hooked into this woeful measuring system, and truthfully, I still have some hooks there, and it makes no sense, given what we are dealing with, in this moment in the history of the world. Artists need to step out of line, and break with this pattern of seeking recognition through the status quo, and find other ways to offer their gifts to the world. Still, there is no question that it’s a hard row to hoe. We will get into this in later posts.

In 1984, the best path I could see for my passions was to teach and raise the consciousness of college students. I wanted to inspire them to use art to tell their stories, to shift people’s thinking, open up closed minds, wake up numb hearts, heal trauma, and envision a different world. I did not feel confident in competing for the few teaching gigs in NYC because I wasn’t a white man with a celebrity career; I knew I needed to look for a position in a college town somewhere in the hinterlands. Because of the recognition I’d already received, I was being invited to give talks about my work and activist art on college campuses. So I just needed to find a place that was looking for what I had to offer. I applied to what seemed like the perfect position at Bard College in upstate NY. When the rejection letter arrived, I felt the normal disappointment, but decided to redouble my visualization process. A week or so later, I received a call from my alma mater where I had given talks the year before. They said, “one of our faculty members just received tenure and asked for an emergency leave. She freaked out because she has never been outside of academia. She is moving to Brooklyn to become an artist full-time, and you were the first person we thought of who could take her place. Can you come here as a visiting artist in September and stay for the year?” Kismet. We were trading places. I wasn’t thrilled about spending a winter in Minnesota, but I was already packing my bags and saying good-bye to Brooklyn. This was the brass ring I needed to compete for teaching jobs in the future, and I wasn’t going to let it go.

What a wonderful Sunday I just spent with you! And now yet another CLIFF HANGER to await . . . BRASS RINGS in Minnesota.

The tree outside my window at Blue Mountain Center MELTS ME

THANK YOU for the introduction to Charles Frederick

Your introduction to Joanna Macy makes me SMILE & FEEL HOPE

I WORRY about your foot

Over and out 🤿

I do so love these memoirs of your life and the steady grounded cadence that encapsulates your wisdom, aliveness and striving . It might take me a minute to get round to reading but it always feels so intimate. Thankyou Beverly.