My tools for breathing into the present moment have become crucial medicine for moving through this time rife with crises. I’m not going to detail the collective messes in which we are swimming right now. Instead, I want to suggest that we all need to find our ways to breathe through them to arrive at a form of “gravity humming” and then attempt to transform ourselves within the pain of this time. Maybe find a cohort in which to do this…a living or ancestral one. A part of me knew this instinctively as far back as my Brooklyn days as you will soon learn.

As I breathe, this question arises: “why write about this period of my personal history in this particular moment?” What can this process offer me and you? I’ve come to the conclusion, at least for today, that this writing is a meditation in which I can better understand the confusions and self-doubts which lined my journey during those early years in Brooklyn. I also continue to hope that this writing will lead readers to ask questions, all kinds of questions, but especially ones that help them imagine different pathways for our creative gifts.

What I began to uncover during my four years in Brooklyn was the dilemma of being an artist within capitalism and what I might choose to participate in, succumb to, or reject within that realm. Much of my early path is now obsolete and inaccessible due to the vastly different economics of living in NYC. The ability to work part-time to pay for the essentials, then make art and have enough resources and space in which to make it is not an available pathway to anyone except the wealthy now. Also having sufficient free time to get inspired by schmoozing with others, spending time in nature, or researching things, again is a blessing that very few artists have.

While my resources were very limited during the first two years in Brooklyn (I call them my rice & bean years), I was able to patch together a decent enough artist’s life similar to what I describe above. Taking it to the next level, as many of my peers were doing, by getting a dealer and becoming more commercial, was really uncomfortable for me to imagine, much less do. Perhaps I knew from the get-go that this model of success was not my path, but my ego was both confused and entangled with a version of dominant culture’s vision of how to be successful.

What I was perceiving as success then has shifted over the years, but many aspirations have remained steady. Unlike some of my peers, a solo retrospective at a major museum and a coffee table book featuring one’s art was not the carrot that I was chasing or I didn’t think it was. Seen through the murky haze of memory, I see that I mostly wanted to find community through my work; folks who made me feel less alienated and folks who could teach me things. As my political awareness grew, I wanted to wake people up to things that I thought many were not seeing due to their privileges, their busy schedules, their denial, or their lack of critical thinking. And although I wasn’t able to articulate this at the time, I was also healing many traumas, both epigenetic and from my early life. This mix of intentions was not out of sync with the cultural pulse of that moment, but I was confused about what I really wanted to receive in return, other than the ability to continue my work. The encouragement of well meaning friends pushed me to prove myself worthy in a context I didn’t fully understand. As the reader will learn as I continue this narrative, the context in which worth is determined and felt are key to this story.

The tangle of this very busy time in my early art career was temporarily thrilling, but the glamor began to sour as time went on. The economics of living in NYC in the early ‘80s created a competitive spirit among many artists. The opportunism that began to assert itself more explicitly began to corrupt the initial camaraderie that I had felt and expected; sadly even among a few of the activist artists who I had begun to meet and with whom I collaborated on occasion. In retrospect, my expectations about what would unfold in those early years was probably influenced by some romantic histories of artist salons where creative folks mingled and cross pollinated in ways that were fruitful and unsullied by the stains of capitalism. Yes, naïve, I was, but I was determined to make a difference through the content of what I was sharing.

Let me take you to a particular conversation in 1981: I’m sitting in my mother’s kitchen in small-town northern New Jersey sometime after Reagan was elected when she says to me, “your anxieties about nuclear war are not healthy. I suggest you see a therapist.” I quickly responded saying, “those who are not anxious about this issue need to see therapists.” It was another impasse in our communication. She had always seen me as “overly sensitive.” Early on I found that label insulting and abusive, especially since she seemed to have no idea about the psychological impact of participating in the “duck & cover” air raid drills happening in public schools at the time. The latter were designed to placate that idiot masses in an attempt to offer the impression that our government and other officials were doing something to avert the Cold War’s nuclear threat. Instead a whole generation of school children were traumatized. I felt very much alone with my fears about living in the basement, counting cans of food in the pantry and imagining how long they would last if the bombs did drop.

Thankfully, the fears of this “overly sensitive” daughter were transformed into drawings, installations, and audio pieces. Sadly, my “preoccupation” with these issues was deeply agitating for my mother (not to mention my choice to be an artist). At that time, I didn’t have support materials or folks working with similar content to share with her. I was operating out of my instincts, without a group of fellow travelers standing next to me to validate my concerns It would take me another two years before I found the organization Interhelp, the anti-nuclear movement, and the writings of Joanna Macy.

I was about to exhibit THIS IS NOT A TEST, my installation about a nuclear nightmare, for the second time. Curated by Catherine Allen, Judith Chiti, and Linda Hill, the NY Feminist Art Institute invited me to be part of an exhibition at the Art Expo’ in the NY Coliseum with an amazing cohort of artists who included, Dotty Attie, Nancy Azara, Jennifer Bartlett, Louise Bourgeois, Judy Chicago, Agnes Denes, Mary Beth Edelsón, Janet Fish, Harmony Hammond, Anne Healy, Donna Henes, Yvonne Jacquette, Lois Lane, Pat Lasch, Christine Martens, Ana Mendieta, Beverly Naidus, Alice Neel, Deborah Remington, Faith Ringgold, Betye Saar, Miriam Schapiro, Joan Semmel, Nancy Spero, May Stevens, Michelle Stuart, and Hannah Wilke. I love listing the names of those inspiring women artists. Yes, I know it’s an ego thing. I’m proud that I got to be part of that world for a time.

Aside from being delighted to be in such impressive company, I was eager to see what my installation about nuclear nightmares (first created and shown as my MFA exhibition in Halifax, Nova Scotia) would provoke in NYC. Placing my work in that context, with such diverse artistic expressions in a major convention center in midtown, could have been a real challenge, but the contrast between my work and that of the others, proved to be fruitful. The local news was so intrigued by my piece that they interviewed me for prime time t.v. asking why I was so concerned about nuclear war. I remember being a bit concerned by the questions being asked by the interviewer. His queries indicated that he was oblivious to the reality we were living in, and that he expected that his t.v. audience was as well. The mainstream was still deeply engaged in the numb bubble that many of us still live inside, one in which we imagine that the nuclear weapons continually on alert, do not exist, mean us no harm, or conversely, we know that they will wipe us out instantly, so why think about them. It would be two more years before “The Day After” (literal trigger warning here) screened on a major television channel and sent unwary viewers into panic mode (radio talk shows indicated that this was the most common response) wondering where they should move to in order to avoid the fates depicted in the film.

Some anonymous visitors who came to THIS IS NOT A TEST really listened to the dialog in the audio and felt seen and heard: they left me hand-written messages under the bed sheets in the installation, saying, “thank you for speaking a truth that I’ve been feeling for years,” and “you hit the nail on the head. I’ve felt so alone with these thoughts.” Seeing that my work provoked such responses, not just conversations about the fears evoked during the Cuban Missile Crisis, as the original installation did, gave me pause. What if I explicitly asked the audience for these kinds of responses in the future? More on that question as this narrative continues.

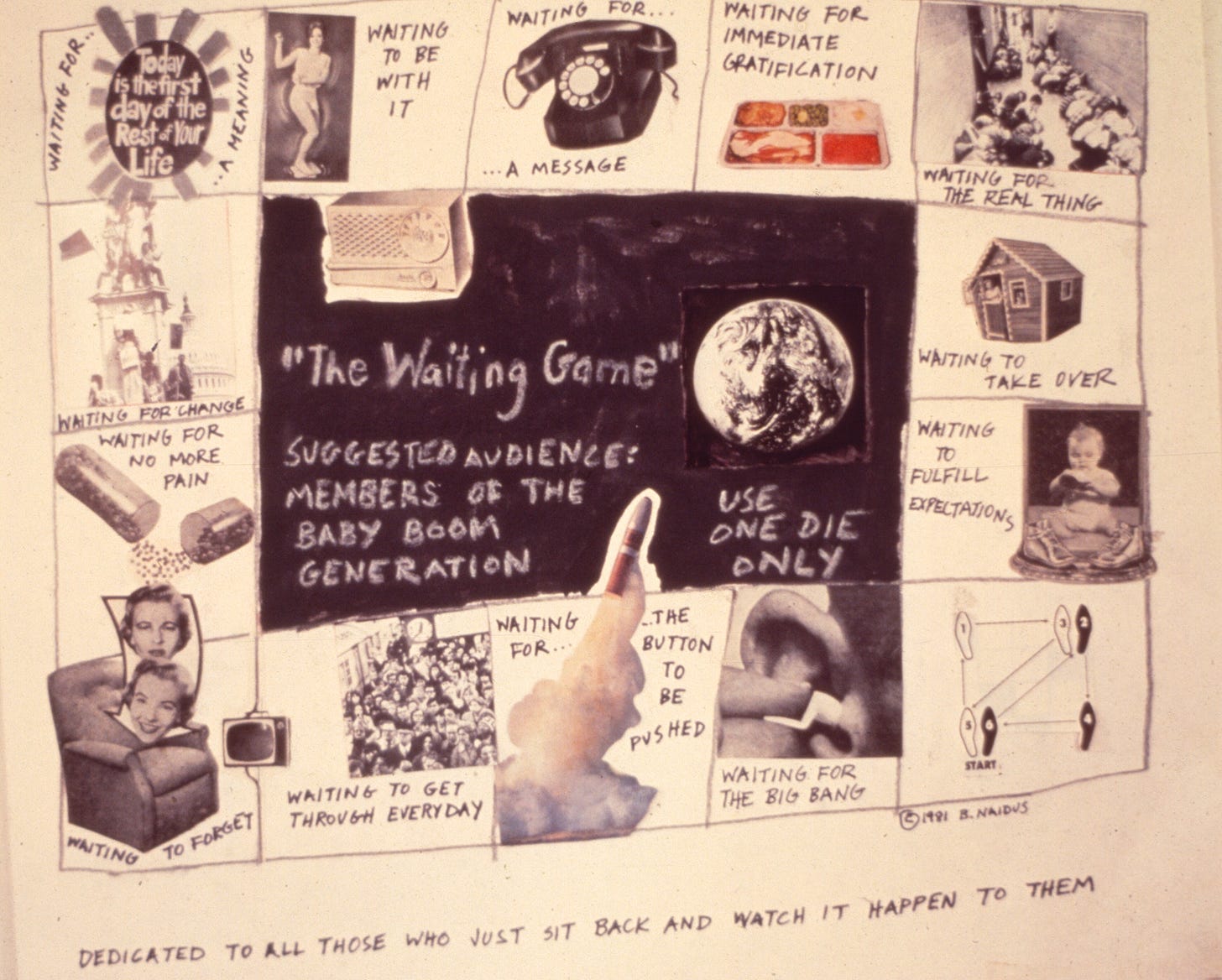

As a result of “being in the right place, at the right time, with the right thing,” over the next four years, I was invited to participate in dozens of group shows all with socially engaged and ecological themes. Maps of elaborate game boards, drawings of installations, and proposals for public interventions were common threads in this work.

“The Waiting Game,” Collage and ink, 1981, published in Heresies #14

The exhibitions were in new alternative spaces in NYC, established galleries, college lobbies and art centers, and museums. The themes varied, but were almost always critiquing the status quo and transgressive in some way. I began to carve a niche as someone who combined humor while offering strategies for subversion in everyday life.

Through one of these shows, I met two of the facilitators of Carnival Knowledge, Lyn Hughes and Anne Pitrone. Lyn invited me to help her create a participatory game (she had decided on a ring toss game where participants tossed coins onto a bed of roses). Her concept satirized patriarchal marriage. She had been married while I had not. I think the piece was definitely therapeutic for many participants, but for me it was more of a visual problem solving experience; I already knew that a patriarchal marriage was not happening in my future. This first art collaboration was fruitful and I found that working with the group and Lyn was deeply rewarding. It pains me now that 40 years later we have to regroup in relation to reproductive rights to fight the repressive backlash.

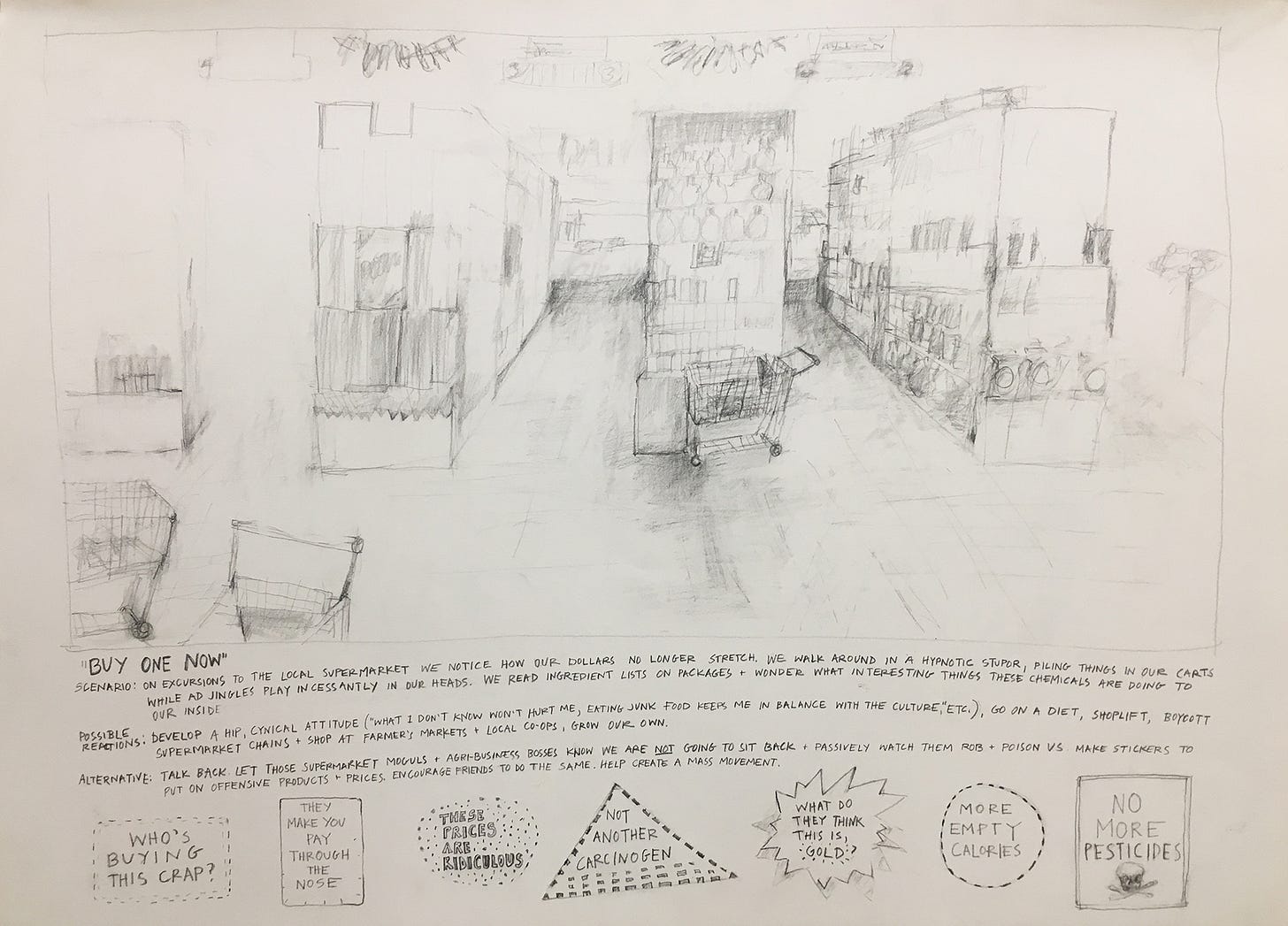

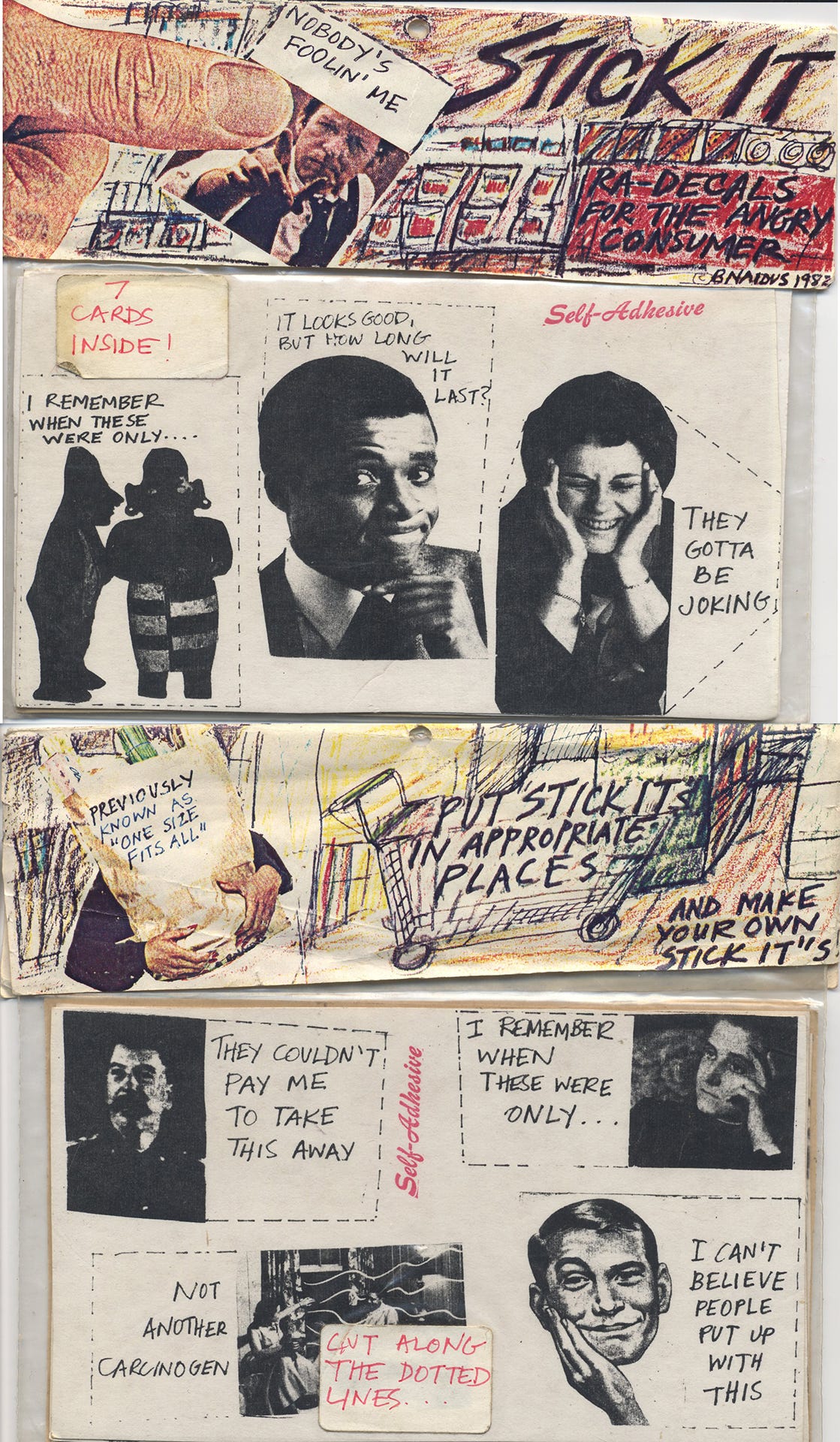

Two other projects define this period for me. One was “The Empire’s New Clothes,” (later retitled, “Taking the Empire’s New Clothes to the Laundry”). It was a series of drawings of everyday locations with text prompts about how to interrupt the trance and subvert within those places. A product that emerged from two of those drawings (of the supermarket and the department store) was a package of stickers called “Stick It’s: Ra-decals for the Angry Consumer.” I can thank Mike Glier (who later became the husband of Jenny Holzer), of Colab, for pushing me to work on that project. I also received a small grant to help it emerge. “Stick It’s” were very popular with the high school students that I worked with at the time. Occasionally I would see them showing up on the poster ads in subway stations. About two decades later, the San Francisco Mime Troupe performed a play where the Stick It’s were used as a prop. I introduced myself to them, and thanked them for keeping that energy of the stickers alive.

“Buy One Now” (from “Taking the Empire’s New Clothes to the Laundry” Graphite on paper, 1982

“Stick It’s: Ra-decals for the Angry Consumer” Self-adhesive stickers (35 per package), 1982

Both of these projects helped me find peers, as these pieces were curated into shows with other artists combining humor and politics in their work. I suggested to one of the women artists that we meet and talk about the challenges of doing the kind of work we did, and we invited four other women to join us. We met on a regular basis in one artist’s loft on Canal Street. Informally, we called ourselves “Not Funny Enough.” Our conversations ranged from how to actually “make it” in an art system that was rigged in a wide variety of ways. I remember one discussion when we listed the contemporary women artists who were known to us, who were written about in books and articles, all of whom had either married or were girlfriends of successful white male artists. While it was becoming more visible that a new feisty generation of women artists was attempting to shift things, the paradigm of what it meant to “make it” was not. It came with this realization: Why did we want a bigger slice of a rotten pie? I was likely the most radical and idealistic of our short-lived club, so this question did not garner a lot of traction. We met off and on for about two years, and we all went on very separate paths. Two of the founders of “Carnival Knowledge” became more pragmatic about their creative careers: one became part of a burgeoning group of female toy designers and the other became a successful high-class wedding photographer. Another photographer in the group continues to show her work and is now a goat farmer and cheese maker in Vermont.

One of the artists in our group went on to co-create the Guerilla Girls, a collective who became an important voice in naming the sexism and racism of the high art world. Despite engaging with a subset group of GG called Mothers of Medusa (MOM) after moving to Los Angeles, my relationship to their work is a challenging one. I do appreciate that they’ve been alerting the public to the gross inequities in both the high art world and within the entertainment industry. It’s definitely important that systemic oppression is revealed wherever it exists, but these problems exist inside a system where reforms are definitely not enough. We need a complete overhaul, a redo, or as I’ve said in many talks over the years, “we need to bake a new pie.” In upcoming posts, I will be sharing some of the new pies that I’ve been discovering and tasting in the past few years. In the meantime, subverting within the system we are currently in is a path many of us have taken - it should come with a warning label that says, “recipe for burnout.”

As rents began to rise, the shadow of the commercial art market began to assert itself in every corner of the “alternative art” scene that I inhabited. The sense of power that some artists seemed to glean from rubbing shoulders with those who were “known” at the Mudd Club, CBBG’s or Max’s Kansas City, felt mostly toxic to me, although I was not immune to it. With a body that didn’t much enjoy alcohol or staying out until dawn along with a budget that was very limited, I was relieved of this duty. I did get to experience the Mudd Club once when I was asked by Martha Wilson to emcee a fundraiser for the Franklin Furnace there. My lasting memory of the experience was a very gray space filled with very gray faces, occupied with expressions of utter boredom. It was nihilism on steroids. I was grateful for being spared that kind of misery. Anyone who reads the recent article in The New Yorker about the rise of Larry Gagosian in the mainstream art world will understand why many of us began to perceive that the NY art scene was no longer where we belonged.

Witnessing the “successful” career trajectories of some of my peers offered me lessons about who and what I did NOT want to become. I was rescued from that pathway by some very good fortune that I will detail in my next post.

But before I go there, I want to share a bit about how I found some better strategies for surviving in NYC (just before I grabbed the brass ring that allowed me to leave).

In 1980, I had found work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and was happily teaching art as a subversive activity (the link here is to my first published essay in Radical Teacher - it’s not my best writing, but I’m glad that I had the courage back then to write). The gig at the Met led to work at the Guggenheim, and eventually to MoMA and the Brooklyn Museum. I developed a passion for deconstructing what was on the walls in relation to sexism and racism, while helping public high school students make their own work about their own values. I threw in a bit of media literacy (courtesy of the then new Canadian magazine, Ad Busters). It was great to be “allowed” to teach this curriculum (my supervisors never really knew what I was doing) and I loved working with the students, but I needed to develop other skills so I could pay my rising rent and diversify my diet. My earnings as a teaching artist were meager - $25/hour for 6 hours per week.

A friend suggested that I learn “paste-up and mechanicals,” a now extinct graphic design skill (it’s been replaced by digital applications) that involved using a t-square, a triangle, and rubber cement. It required a certain kind of precision with cutting straight lines that was not my forté, but I persisted, and in a three-week course, I had a sufficient portfolio to make $15/hour for a catalog company. It was excruciatingly boring work, but I finally had a decent paycheck. I expanded my remedial art education to include courses on typography and illustration at Parson’s School of Art and Design, and was able to get more work assisting graphic designers. Through my friendship with the late Jacki Apple, I was able to secure steady work with my absolute favorite employer, Sara Seagull. She created the designs for the publications of museums, alternative art spaces, and a few magazines. It was never boring, and the pay went up to $25/hour. I was finally financially stable and feeling grateful for a good working situation.

To add to this sufficient income, Mike Glier (who I mentioned above was an important source of encouragement during this time) was trying to inspire me to find an art dealer, and recommended me to Annina Nosei among others.

Annina arrived two hours late to my Brooklyn loft, breathless, saying that her driver had gotten lost in Brooklyn, and that she had stayed longer than expected visiting with Jean-Michel Basquiat. She then proceeded to tell me, in her excited Italian accent, that she was going to lock him in a basement studio with art supplies for the summer so that he could produce for her gallery. I was horrified hearing this. She looked casually at my work, saying that she would give me a show in the fall (it was springtime) if I could make these very small works on canvas and paper much, much bigger - otherwise she could not pay her rent. Again, I was dumbfounded. I understood her predicament, given the high rents in Soho, but I was not making shoes in different sizes. I thanked her for her visit. She invited me to a party that she was having for collectors and artists, and I went. When I discovered that the topics most collectors were engaged in were about their investments, their real estate, and their legal problems, it became very clear to me that this was not my world.

I did have a few more studio and gallery visits with an assorted bunch of not particularly amiable or intellectually engaging dealers; none of those visits amounted to anything worth reporting here. I was vainly looking for my Alfred Stieglitz in a time when most gallerists were interested in the latest trend, like graffiti artists, and collectors had mostly shifted to an investment mentality. I did not want to be packaged and marketed, at least, not on someone else’s terms or by someone whose values were so opposed to mine. I wanted to subvert, intervene, and break the trance. Thankfully an invitation from the Blue Mountain Center in the Adirondacks arrived at just the right time where I would meet a diverse cohort of peers who had similar ambitions, and I was able to imagine new pathways for my future.

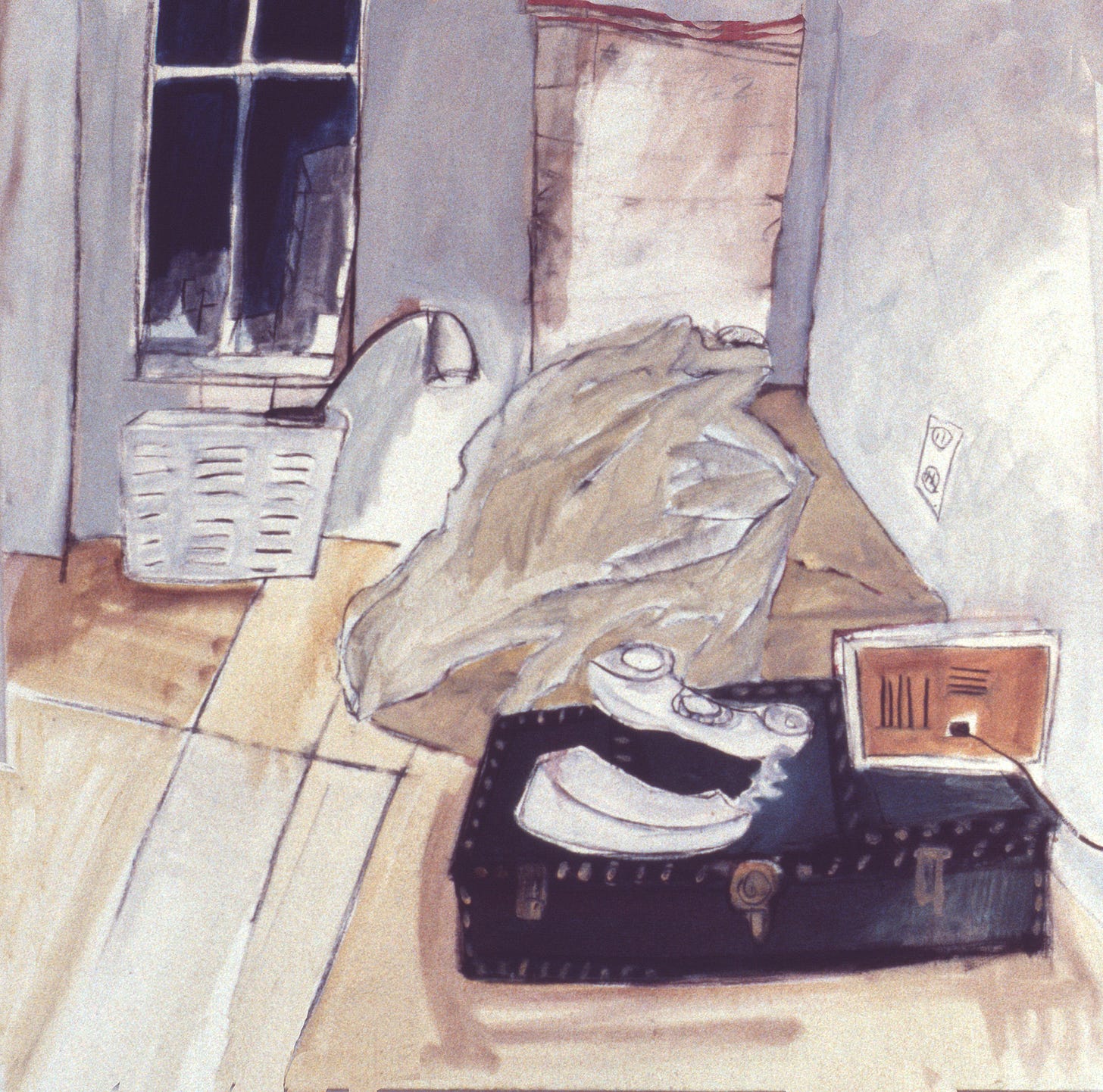

Before I leave this “episode” in my Brooklyn life, I want to share two of the more personal paintings that I created during this time of intense self-reflection. I had started therapy, and my journals from that period examine all the contradictions and cognitive dissonance leaking from my daily life. The two Phone Series paintings below have never been shown publicly. They remind me of the angst of that time and speak to my instinctive desire to self-transform in the midst of the absurdity I was experiencing. The first one is in the private collection of friends, and the other has disappeared, lost to time, but not to cyberspace. If you’d like to see a few more pieces from this time period, go to this link.

Wow Thankyou for treading backwards into the water and revisiting your struggle / efforts.

Beverly, your story is so interesting. It is wonderful to learn more about you. It reads like fiction in the sense of the cultural, historical, social influences on the collective seems so "out there", yet it is very real, (and always is) just as your experiences reveal. I wonder if synchronicity is something you have thought about and appreciated.