The Perils of Attention (Part 2)

One bitter cold, wintry evening, while walking across the campus during my junior year in college, I stood on a frozen bridge, gripping the railing, and made a wish while gazing up at a star-filled sky. I'm not sure what passion, need, or resentment fueled this gesture that particular Minnesota evening, but it is seared into my memory bank. Quietly I whispered the words of the corny nursery rhyme: "Star light, star bright, first star I see tonight, I wish I may, I wish I might, have this wish, I wish tonight." Rituals that involve wishing had become my form of praying, and despite growing up in a home without religion, this had become my secret practice. By age 20, it was shaped by both instinct, innocence, and an abiding faith in something outside myself. My secret wish was to become a significant artist someday and that my art would make a difference in the lives of others. I was determined to make this wish come true; I felt I had a mission to fulfill and I wanted to prove to certain others that I had more to offer the world than they imagined me to have.

During my college years, my relationship to my creative work shifted in many ways. I became more attuned to how my art was helping me process my trauma, and more conflicted about how that kind of work was going to help the world or sustain me as an individual. Art classes were my anchor in the midst of that confusion, but there were some unexpected challenges in those waters that I will detail in a bit.

Our liberal arts college offered me the opportunity to explore other possibilities besides art. Paul Wellstone’s political science class reignited my passion for activism. I had received an unexpected and early dose of cynicism after campaigning for Eugene McCarthy, the progressive presidential candidate of my high school years, but Paul’s idealism and his success at building grass roots coalitions inspired us all.

I loved anthropology, and while doing research on alternative child rearing possibilities for my teacher, Paul Riesman, he got me hooked on journaling and that habit has served me for a lifetime. What discouraged me about majoring in anthropology was the possibility of being required to take a course in statistics, the idea of doing foot-noted research papers for the rest of my life was not attractive, and the idea of going into another culture as an outsider to “research them” was unappealing. The discussion of being a cultural imperialist or a colonizer was not visible in the readings we did, but I felt these conflicts intuitively.

I briefly tried to be practical in my studies. My first geology teacher, Eiler Henrickson, was fascinated by my love of rocks and deep time, and encouraged me to pursue a major in geology, but when I learned that most “geo jocks” went on to work for fossil fuel companies, I ran in the opposite direction. If an ecology major had existed at my school in the early seventies, I might have moved in that direction, but such a thing did not yet exist. The same was true for women’s studies, communications or media studies - none of them had been hatched just yet.

I tried classes in linguistics, education, psychology, and sociology, but none of them were taught dynamically enough for my needs. I loved my history and literature classes, but I knew I didn’t have any interest in writing endless research papers, and eventually a dissertation. So I just saw those classes as windows into worlds that would feed my creative work.

Art would be my umbrella under which I could learn about every subject and translate those bits of knowledge in various ways. My involvement in other art practices (dance, theater, and poetry) became tenuous as I was forced to choose one form in order to “major.” Interdisciplinarity was not yet a thing, except in the heads of those of us who could not do otherwise. I kept on writing, as it was essential to my mental health and growth, but that practice was hidden in journals.

In between classes, I could often be found in the studio art building’s lounge, reading the latest art magazines. It may have been there that I first caught the bug that made me think I needed to see my work in those pages in order to know that my art was valuable. Or it may have been meeting young ambitious artists who came to teach at our school with egos that could fill a room. I was strangely attracted to that way of shining. It felt tantalizing and powerful. I did not know yet how to critique this manifestation of ego.

One day, my printmaking teacher, Dean Warnholtz, an old veteran who had studied with the Argentine, political printmaker, Mauricio Lasansky, took me aside and said: “you’re not like the other female students. I’m going to give you a litho stone to work on. I only give those to serious art students, and all those girls (sic) are going to marry well and purchase our art some day.” I looked at him uncomfortably flattered, bewildered, and disturbed. I didn’t know how to respond. Years later, I recognized that he was inviting me to join the Boys’ Club and be a queen bee. His belief in my ambition felt a bit nasty, like something toxic had been smeared on my skin. I didn’t want to be separated out; I wanted to be with my women friends. I took the litho stone and stumbled on it, too intimidated by the pressure of having to prove myself worthy, my muses ignored me and I made a dud. To this day I have no memory of what the imagery was.

But here’s the good news: the female students & I banded together; we created a feminist support group, organized an exhibition, did a sit down strike in the chair’s office demanding funds for visiting women’s artists, performances and poetry readiings, and inclusion of women’s art in the art history classes, etc. We were inspired by news of the Feminist Art Program at CalArts, though without the internet back then (1973), we must have learned about through word of mouth.

Every one of us became a professional artist of some kind. We gave each other support at a crucial time in our lives and our version of mutual aid has stuck with me over the years.

Also the art department was changed forever by our protests. Women art faculty in studio and history were hired, first as temporary appointments and later as tenure-track and tenured, and by the time I came back to campus as a visiting artist in the mid-1980s, I saw that artists of color and women were clearly valued in the art history classes.

What was not addressed and probably still isn’t, is how success is measured in an artist’s life. Many art programs in colleges and universities began offering courses on how to survive as an artist by the mid-1980s, something that was not discussed much when I was an undergraduate. But the emphasis on portfolio development, marketing, networking, etc. never questions the status quo, how economic class and art making sit together, the gate keeping in the art world, and how artists’ personas become more important than the work they create when we enter that commodity-driven world. Nor are the values of art as a spiritual journey, as a tool for waking people up, for creating community, for inviting dialog, for documenting the invisible, or for healing, a significant part of these kinds of courses.

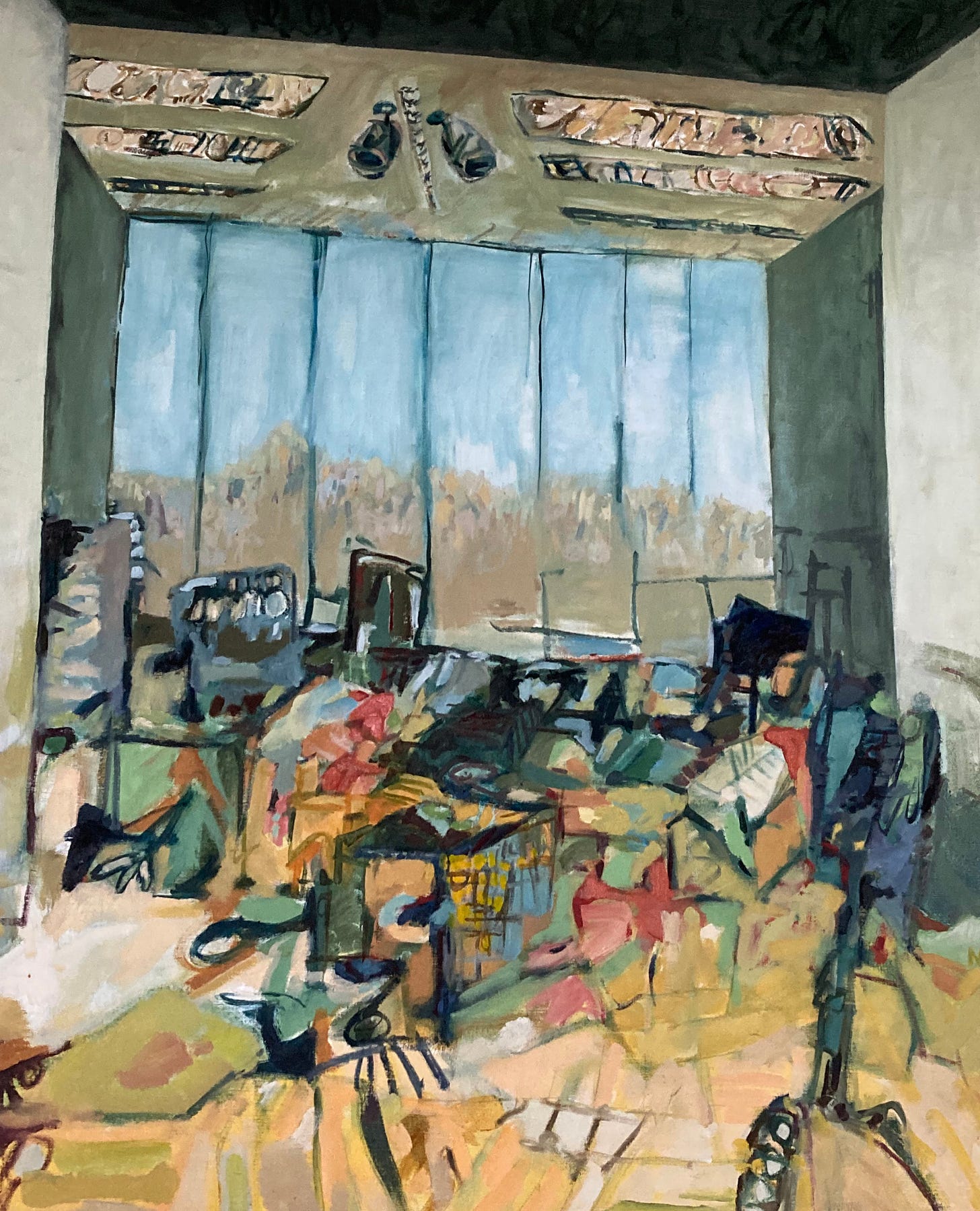

Boliou, the Art Studio, 1975, oil (in the collection of Anne Petrocci & Richard Vincek)

In retrospect, I can see that my printmaking teacher, Dean Warnholtz, meant well, but his praise did not serve my healthy ego development. He was operating out of an older patriarchal paradigm, and saw his role as a gate keeper. Still I must mention one important recommendation that he offered me; it nourished an important vision that I carried into grad school and beyond. He suggested that I read Ben Shahn’s The Shape of Content. This was the first time that I had read the story of a socially engaged artist devoted to teaching and making work as service to the world. Shahn didn’t use the term, Tikkun Olam (Hebrew for repair and improve the world), but his philosophy of art reflected a deep respect for social justice movements and the contributions that artists can make to them with their work and their approaches to pedagogy.

Unfortunately, my role models for being a confident, yet open-hearted, curious female artist were sparse. One of the feminist artists we brought to campus was dogmatic and essentialist in her approach to feminist art. She seemed too full of herself, authoritative in an unhealthy way; I did not want to mimic that attitude, and was eager to find other women artist who could inspire me. It would take a few years to find them, and would take even more years to have compassion for the feminist artist who developed this harsh persona in response to her wounding within patriarchy.

As I continue interrogating how the ego of an artist develops, I want to look at what makes one shift into what might be perceived as arrogance, or in its extreme, egomania or narcissism? Is it always the oppression of patriarchy that motivates the desire to claim more space for oneself or is it purely insecurity? How does one find the strength and courage to create an art practice that is both of service to others and provides for one’s basic needs, without compromising one’s ethics?

In my next post, I will look at how my first tastes of the NY art world conspired to make me yearn for a certain kind of glory (the economics of living in NYC were a big part of that desire), and then how my graduate education in Canada helped me keep my sense of mission while fueling my desire to be a subversive teacher and artist.