Perhaps it’s fitting that I used the last drops of “grief oil” to massage my feet a couple of weeks ago, as I was beginning to dive deeper into the Tamera experience through this writing. My dear friend, Thea, sent me this oil after Bob died. I kept the vial on my ancestor altar in my home office, and used it for self-massage throughout the year. Writing this post now reinforces the idea that grief never ends. We have rituals to process it, but it remains terrain that will need tending as the years pass. It just gets expressed in a myriad of ways, evoking a complexity of emotions. In our modern society, we do exceptionally poorly at processing this fundamental human experience.

One of the reasons that I chose to apply for the program at Tamera was to go deeper into the threshold represented by this moment, not just my personal grief, but the huge collective one that so many of us have been holding. I wanted to orient myself with others as I entered a new chapter, and as we orient ourselves in this time of overwhelming human and more than human crises.

I arrived at Tamera with a strong drive to meet like-minded souls, as well as a desire to have my own perspective expanded, but I also had a very specific task in mind. I carried a small bag of the nutrient-rich soil made from Bob’s composted body tucked in my suitcase. My intention was to do ceremony with it. I needed to speak to the residents, share this desire, ask for permission, and be led to a sacred site on the land. As I met with the facilitators and my peers in the program, Sacred Activism, the possibility of shaping ceremony with them ripened within me.

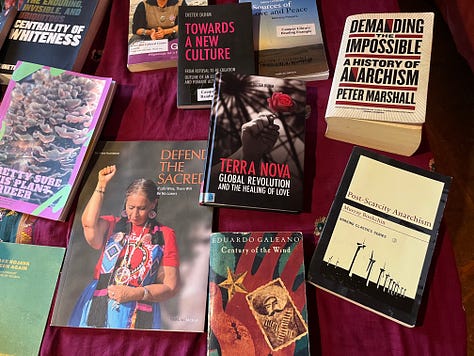

A collaborative mural, created by about a dozen members of the sacred activism cohort on ART MOUNTAIN (a special site for creative expression where there are several protective structures, awnings, tables, a small kitchen, many art materials, and lots of projects in process).

This mural was created spontaneously in an hour on a Sunday afternoon right after I gave a slide presentation to the community about the spectrum of activist art in a time of collapse. June 2024

As mentioned previously, the physical challenges of travel were more significant than expected. I had not experienced such a dramatic chest cough in many decades; it brought back difficult memories of my disabling environmental illness after being exposed to the aerial spraying of Malathion in Los Angeles in my mid-30s. It took almost a decade to heal from it. Being able to transcend those particular feelings of vulnerability in order to participate fully in the program was a significant part of the experience for me. One of the facilitators was particularly kind when she acknowledged that I was trying to repress a cough during a session, and said, “Bee, just allow the cough to express itself and don’t try to control it.” That made me feel completely welcome in the group, with all my body’s imperfections. Thanks, A’ida. <3

Much of the work that we did during the 10 days of Sacred Activism programming was about healing trauma, processing grief, understanding our nervous systems and learning tools for better self-regulation, recognizing our vulnerabilities, and building trust. We shared lots of stories about what we were carrying as activist work, service, emotional baggage, and visions. We did rituals together, took walks to special places on the land, sang, and danced together - all of those things helped us move through the intensity of the research we were doing: how to thrive as activists while grounded in community (both the human and more than human) despite the dire challenges we face on our planet and in our home communities.

During our second day together we attempted to uncover what makes activism sacred, and we came up with this list: dedicating one’s actions for the next 7 generations, feeling the earth, water, air, and fire within us as we do this work, finding diverse collaborators and bridging our differences, generating new courage and strength after each heart break, and giving our systems a chance to rest and renew in ritual and ceremony. As we sat with this list of intentions, we made agreements for reliable participation, mindful listening and speaking, and holding ourselves to be transparent, confidential, non-harming, and open to learning.

Our next day was devoted to trauma work. We addressed collective, historic, systemic, and epigenetic traumas as well as colonization’s impact via racialized trauma and decontextualized trauma (when trauma appears as a personality or a culture). We distinguished Big T trauma caused by natural disasters, war, and abuse, from Small T that might cause codependency and other behaviors and patterns that our creative nervous systems might have conjured up to avoid pain and suffering.

One of many public art pieces on the 300+ acre campus of Tamera.

One of our facilitators, Dara Silverman, a dynamic woman in her 30’s who has lived in Tamera for many years (originally from NYC), explained how the various parts of the brain (neo-cortex, limbic, amygdalla, etc.) process our experiences and some of the details about how our nervous systems work, while leading us through exercises to release what our hypo- or hyper-aroused systems might be holding. Rocking and self-hugging were among some of the methods recommended. She described the four patterns caused by trauma: flight, fight, freeze, fawn, and the behaviors that accompany them. She talked about how we all have natural capacities to process trauma, but that our patriarchal/capitalist society often prevents us from releasing it.

The following day, we worked with a woman outside the community, Saskia Breithardt, who had been leading grief rituals in the tradition of the Dagara people of Burkina Faso, taught to her by the late Sobonfo Somé. I had taken a weekend workshop with Sobonfo over 10 years ago and found it really difficult to break through my mental armor to experience my grief somatically. So I was eager to experience this work while carrying so much grief that was obvious and tangible. The facilitator spoke about the powerful work of Francis Weller and his Five Gates of Grief. I listened to his book during the month after Bob died, and it gave me some deep comfort for the process I was going through. The rituals that we did that day seemed to touch most of our cohort and there were emotional breakthroughs for so many; it seemed that their vulnerability allowed me to release tears more publicly than I had in over a year. After days of feeling that my age, my illness, and my living quarters guaranteed my position as an outsider, I broke through that very old and troubling pattern and finally felt truly connected and held by the group.

As part of our grief work, we did writing exercises inspired by the work of Natalie Goldberg, and completed these sentences: My heart is almost too full…I will not pretend…I am so sad….It is not all right with me…I will try to overcome…..What I wrote in response to those prompts was not new to me, nor was it particularly good writing, but I was glad that this way of working with grief was offered up.

It was especially important that we made space to allow our collective grief to emerge. We were all carrying pieces of it, particularly surrounding the genocides that were and are impacting so many of our cohort. Together we watched the powerful film, Where Olive Trees Weep produced by the amazing Zaya and Maurizio Benazzo and their team at Science and Nonduality (I highly recommend their podcast). Several members in the group had intimate connections with the film and its content due to their heritage or experience. Holding the space for working through our pain and grief together offered some comfort and relief, but there was something that seemed inconsolable when we witnessed one of the members of our cohort’s grief. She was receiving daily texts about the loss of friends (children and their families) and colleagues in Gaza. After she shared this with our group one afternoon, we gathered to embrace her, gently holding each other with love. So much that we are taking in right now is unfathomable, but being an attentive witness can help us process what we are going through.

This recently released podcast has some wonderful insights about tending grief.

One of the intimate ways we were offered by our program’s structure to process our emotions was the formation of “triplets” on the first day. My triplet included a lively young man from Argentina who ran a foundation to help impoverished youth in his country. The other member of our triplet was a bright-eyed young man who grew up in East Germany and who was co-parenting a teenage boy who had been born at Tamera. He had facilitated programs in theater and social change at Tamera. After the morning seminars, we would sometimes come together to share our reactions to what had been presented. As we built trust together, the stories we shared highlighted the traumas that each of us were carrying - disrupted heritages, fractured families, the violence of the systems around us all emerged, as well as a deep desire to heal our communities and ourselves.

A day or two later, one of our program’s facilitators, A’ida Shibli who was born into a Bedouin community in Palestine and who has been a stalwart peace activist living in the Tamera community for many years, brought us a fresh look at indigeneity and how deeply the colonial mindset can claim our view of the world. She flavored our discussion with some rich stories from her own upbringing; it was impossible to not become wistful for what has been lost, especially communities in which elders are valued, where children are co-parented and loved by many, and where mutual aid is the ethic informing daily life (all of this is happening at Tamera). She detailed many ways to decolonize from oppressive systems and how to reclaim nourishing cultural practices that may have been erased by those systems. We talked about ways to reroot ourselves within ancestral lineages and what might be necessary to reconnect with a form of community care that’s often neglected in the modern world. This seminar was held outdoors, where we picnicked and did some exercises reminiscent of deep ecology to help us connect with the more than human. During our silent meditations, we paused and reflected with the vast array of flora and fauna, and later shared our experiences with each other. Given the heat of that afternoon, we did a spontaneous group immersion at the Oracle Spring on Tamera’s land where we sang and chanted together. It was a strong reminder that when we feel most distraught about the state of the world, we can always return to nature and a supportive community to balance our nervous systems.

I’m only sharing photos where my cohort members are not clearly visible. Some of them work with refugees and in conflict zones and a few have been persecuted for their politics, so it’s best to keep their identities private.

During the program, we did several rituals that involved water, bringing intentions for our work together and a splash of water to a bowl in the center of our gatherings. Once a week, there were ceremonies in a stone circle at dawn. I never made it to one of those due to my illness & exhaustion, but others in the group did go and said it was powerful and grounding - and if folks are interested, these ceremonies are visible and audible weekly on Instagram at

Every Sunday morning there was a gathering in the Aula called the Matinee where songs, announcements, and stories were shared with the entire community. There were also night time “rituals” at the Centro Cultural, the Tamera “watering hole” (café/bar) for libations that included musical performances, slide talks, political discussions, dancing, schmoozing, and snacks.

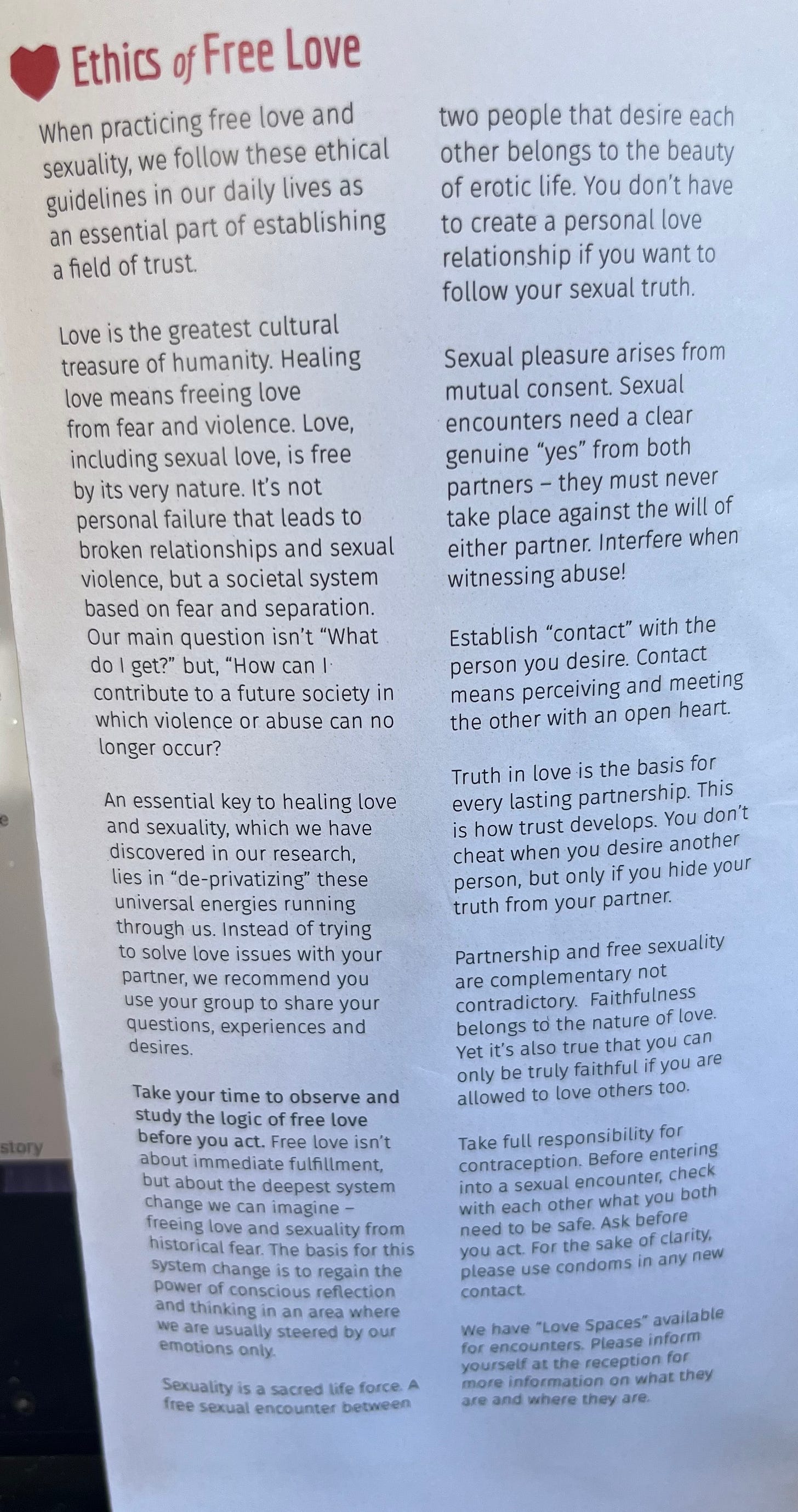

We received another overview of the Love School and how the community’s research in ways to dismantle patriarchy lived within this framework, forming a culture of truth and transparency. A lack of game playing, lying, and passive aggressive behaviors has the potential to create a path towards a less violent society. The brochure given to us about Tamera (see below) offers a partial view into this philosophy. Not all of the members of our cohort felt in alignment with the “free love” POV espoused by Tamera due to cultural and religious differences, but for many, it seemed very liberating.

One of our last seminars was on “system change.” It offered by one of our program’s facilitators, Martin Winiecki. You can hear him speak about sacred activism here. He brought us a cogent analysis of capitalism and described the many systems that are part of the ecocide we and the more than human are experiencing now. His discussion connected economics, culture, worldview, interpersonal relationships, and psycho-spiritual issues that are imperiled by the capitalist model. Rojava and the Zapatista Movement were cited as examples of current attempts to re-imagine the future outside of capitalism, by removing dominating hierarchical systems, dismantling white supremacy, patriarchy & hetero-normativity. He inspired us with stories about what it means to live in a healing biotope that functions as an educational hub and catalyst for other experiments around the world.

On the last night of our program, I was ready to bring some of Bob’s nutrient-rich soil to the ancestor part of the land, Terra Deva. I had arranged with the kind, thoughtful member of my triplet who lives within the Tamera community to make this possible. Terra Deva is where the ashes of Tamera’s community members whose spirits have transitioned off this physical plane are placed along with altars to honor their lives. I asked for volunteers to come help create ceremony with me and was surprised when 15 peers stepped up. Initially I had suggested that maybe four of us would make the journey (it was a long hike) to the sacred space, so we had to negotiate a bit with the kind caretaker when we arrived at the entrance. This gentle woman agreed to let us all in, and shared some stories in her thick German accent about the Terra Deva and its intentions. She led us down the trail to an alcove-like space filled with playful altars, dedicated to a community member named Sylvia, a musician and singer, who died too young (in her 40’s) of cancer. It was the perfect spot for us to gather. The homage to someone named Sylvia was especially resonant since one of my favorite ancestors is my paternal grandmother Sylvia, and I named one of my first cats, a true familiar, Sylvia. That lovely, smart, silver-pelted cat was part of what brought Bob and I together on October 28th, 1988 (his 40th bday).

As we walked to Terra Deva, I invited my peers to gather something beautiful from nature to offer up as part of our ceremony. As we sat in Sylvia’s sacred space, I passed around the bag of Bob’s dirt so that people could touch it, if they wished, and place what they had gathered in the bag. I told some of the stories of Bob’s journey, some of which can be read in his obituary, and people offered songs and poems that created an uplifting energy. I invited three people, each one representing some special resonance for Bob’s life, to join me as we walked deeper into the woods to find a resting place for his soil (see below). We meditated briefly, I said a few words, and felt lighter than I had in years. Some of Bob’s molecules had arrived to a place he was visualizing during his cancer journey, but did not know about, while he was learning Portuguese online. I felt complete and held in the deepest of ways, and truly understood that this ceremony had been a crucial piece of what had led me to Tamera. An unexpected joy flooded through me and was evident to my peers.

I had planned this journey thinking that I would learn more about my long-carried dream of an activist, healing, spiritual intentional community and whether I would find my place in such a world. I discovered something that I already knew: that no place is perfect, and that my own community in Tacoma, as difficult as my entry into it has been at times, required my attention. I learned this lesson in 2019 when I went with a delegation of eco-artists and scholars interested in reimagining the world to spend time in Chiapas, getting inspiration from the Zapatista Movement. When we visited one of the Zapatista communities, the members who met us asked us very directly, “why did you come here? You need to do this work in your home communities.”

I am grateful that Tamera exists and provides a model of what is possible - it’s an important experiment and learning hub. I deeply respect what I observed and participated in there. My feelings about Tamera are similar to what I felt about the socially engaged meditation center, Plum Village in France (we were there in the summer of 1990). There are a few activist/spiritual places where you can rest and regenerate, learn and listen, but they have their own struggles. Right now, I am feeling the importance of committing to the community in which I live, especially after moving around so much due to health and economic issues. I will remain open and curious about possibilities of other pathways as they arise.

It’s important to mention that I also understood this journey as an initiation into the next chapter of my life. It required more physical and emotional strength than I had imagined, but that’s one of the features of initiations. Would I have liked more of something as part of the Sacred Activism program? Was there anything missing? Well, the truth is that I didn’t have capacity for much more than what I received, and some of it was lush, like the deep heart connections and trust that emerged.

Now, in retrospect, if I were to return and meet with the cohort again, I would like to engage my intellect more fully, and really begin to hash out how folks in different countries are navigating the poly-crises: how are they lifting up positive possibilities as they prepare for the next stage of collapse, the rise of authoritarianism, the woeful miseducation of so many and their reactive stances, and the ways that AI and climate chaos will shift things beyond what we imagined. I missed some of the inspiration provoked by strategizing, philosophizing, and visioning that we did at the Institute for Social Ecology every summer over the decade that Bob and taught there. ISE was the place where I really got deep into imagining a post-apocalyptical future, and Bob helped reinforce that POV over the years.

Nevertheless, I am grateful for the work we did together at Tamera and for the way the space was held - it was a taste of healing and regeneration, and it seemed that most of us needed that. Prentiss Hemphill speaks about this process being a necessity for those of us doing the work of social change in her new book, What It Takes to Heal: How Transforming Ourselves Can Change the World. Please listen to or read her book - it’s essential medicine.

Frederick Weihe, one of our program’s facilitators, warned us that returning to the “world” might be a very difficult adjustment after our very cozy time at Tamera where we had built so much trust and felt so much safety. While there, I never took for granted the uninterrupted peace of walking in the dark at night. I often stopped to pause and contemplate the wondrous soup of stars creating a spacious canopy over my head. The calming symphony of frogs & crickets accompanying my meditative walks down the curving, dusty trails offered an ancient form of comfort. Nor did I take for granted the appreciative smiles, welcoming greetings and hugs from my peers in the program. While many of the younger folks were schmoozing late into the night, developing crushes and flirting, I found myself erotically engaged with the natural world and romanced myself with self-care, something that I am continuing to practice, albeit very imperfectly, back home.

There’s lots more brewing in me about what we learned together, but I’ve been getting continual messages from Substack that this post is too long (too bad, Substack). I know that this post is missing some essential spice by avoiding the naming of people, the specifics of what they were carrying, and the sauce of our interactions, but that omission is deliberate (as I shared earlier).

I am grateful that I was able to have some meaningful in-person conversations with folks from the program during my unexpected and recuperative week in Lisbon, post-residency, and that our WhatsApp group allows for more processing. Our continued connections are bound to be disjointed and infrequent, given the geographical distances and our busy lives. Hopefully all of us are cooking up visions with what we learned and will collaborate at some point in the future.

Well, that was a good one to read Beverly. You have painted a clear picture of your journey through grief and loss and sickness to rituals in Great Nature with myth making supreme. And the story was a circle that brought us around it into the now so thanks for the ride through such thoughtful territory...

I love yer heart

Hmmmmmmmm what a wonderful journey. Thank you for the ride that ended under the soup of stars in the symphonic dark. My mind is full of the 5 gates of grief, weeping olive trees, deep ecology, stone circles, biotopes, what it takes to heal and Bob nurturing Tamera. Thank you Bee for this honey only you can make.