Modernity's Minions Bank with "Banksy"

Or another example of how almost everything can be co-opted

All museums are tied to some sort of corruption - stolen indigenous artifacts, solo shows for the collections of Board members to increase their collections’ value, and various forms of nastiness to reinforce the hierarchies of the status quo. It’s possible to subvert within museum spaces, as I did when I worked as a teaching artist at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in NYC, but even the subversion can eventually be co-opted as something cool and hip produced by the museum, neutralizing its radical edge. The liberal path of reforming bad things ultimately does NOT do much to change the entrenched behaviors that exist in those spaces - such is the imperative of colonial capitalism.

Rather than sounding like the very jaded cynic that I can be, at times, I want to provide the perfect example of how political art can sometimes get digested and spat out as a trivial hipster commodity in our very oppressive, economic system. And that example landed in my lap during my recent trip across the pond.

As you probably know, assuming that you read some of my previous posts, I was in Portugal in June, participating in a program called “Sacred Activism” at the intentional community, Tamera. The week after that 12-day program concluded, I unexpectedly spent a week in Lisbon recovering from the physical strains of travel. I was grateful to have the company of a few of the Tamera cohort for several dinners and one lunch that continued into a delightful walk & conversation through one of the older neighborhoods in Lisbon. During the day, my body eschewed most tourist behavior due my exhaustion, but I did feel compelled to take a break from writing by walking to a few museums to take in some of the local “high” culture. The Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, a vast, modern space filled to the brim with precious treasures from many eras and cultures, had me researching the life of the man who accumulated such extraordinary fossil fuel wealth that allowed for such an overwhelming number of acquisitions. I also went to visit the home of Gulbenkian’s doctor, The Casa-Museu Dr. Anastácio Gonçalves, that has been turned into a museum. I was most amazed by the ornate writing desks and cabinets designed for the accoutrements needed for correspondence. I thought the desk in my home office space would definitely be enhanced by such furniture, but how would I find anything without the crazy spillage of piles on my desk?

During my last full day in Lisbon, I was joined by one of the Tamera cohort, a German journalist and painter, Elisa, who lives in Mallorca. Despite the heat of the day, we decided to check out this museum with a concerning appellation that was walking distance from our hotel, the Banksy Museum.

Before arriving at this jarring façade, I shared with Elisa that I had low expectations about what we might encounter in such a museum. I couldn’t imagine that Banksy himself would have created such a place to archive his work. His work is best digested in its ephemeral form as a visual gesture/provocation in public spaces, the context always considered in relation to the content of what’s being painted and exposed.

When we entered and paid admission (8 euros for seniors, 12 euros for Elisa), I asked the young woman taking our money who owned the museum, whether any of the profits from shop sales and admission fees went to Banksy, and what the intention of the museum was. It was already obvious that the reproductions of Banksy’s work were low quality, and after she responded, saying that Banksy did not own the copyright on his name or work, it was clear that the intention was to make money off his celebrity. She defended the project by saying that this museum brought his work to a larger audience. It seemed like a brazen enterprise, and what really irked me was how the cheesy presentation of his work seemed to trivialize his interventions in the worst way.

In discussion with Elisa, I realized that many people may not be aware of some of the social issues that his work addresses. It’s hard to fathom how thick the blinders of contemporary tourists and museum goers might be, but we do live in a culture that encourages numbness and distraction via superficial entertainment. Perhaps I should not be so surprised that people are unaware of homophobia, police violence, religious fundamentalism, war profiteering, environmental pollution, the despair of the youth, the repression of resistance, etc. I had to grudgingly admit that there may be some benefit in exposing people to social issues that they have not been exposed to, but ultimately it still feels very superficial.

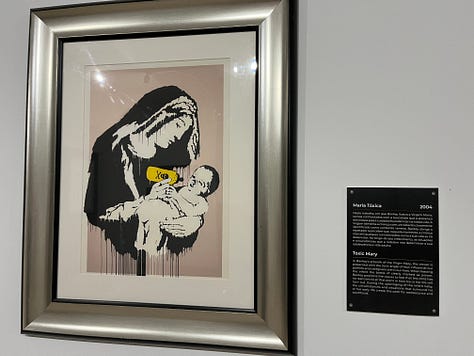

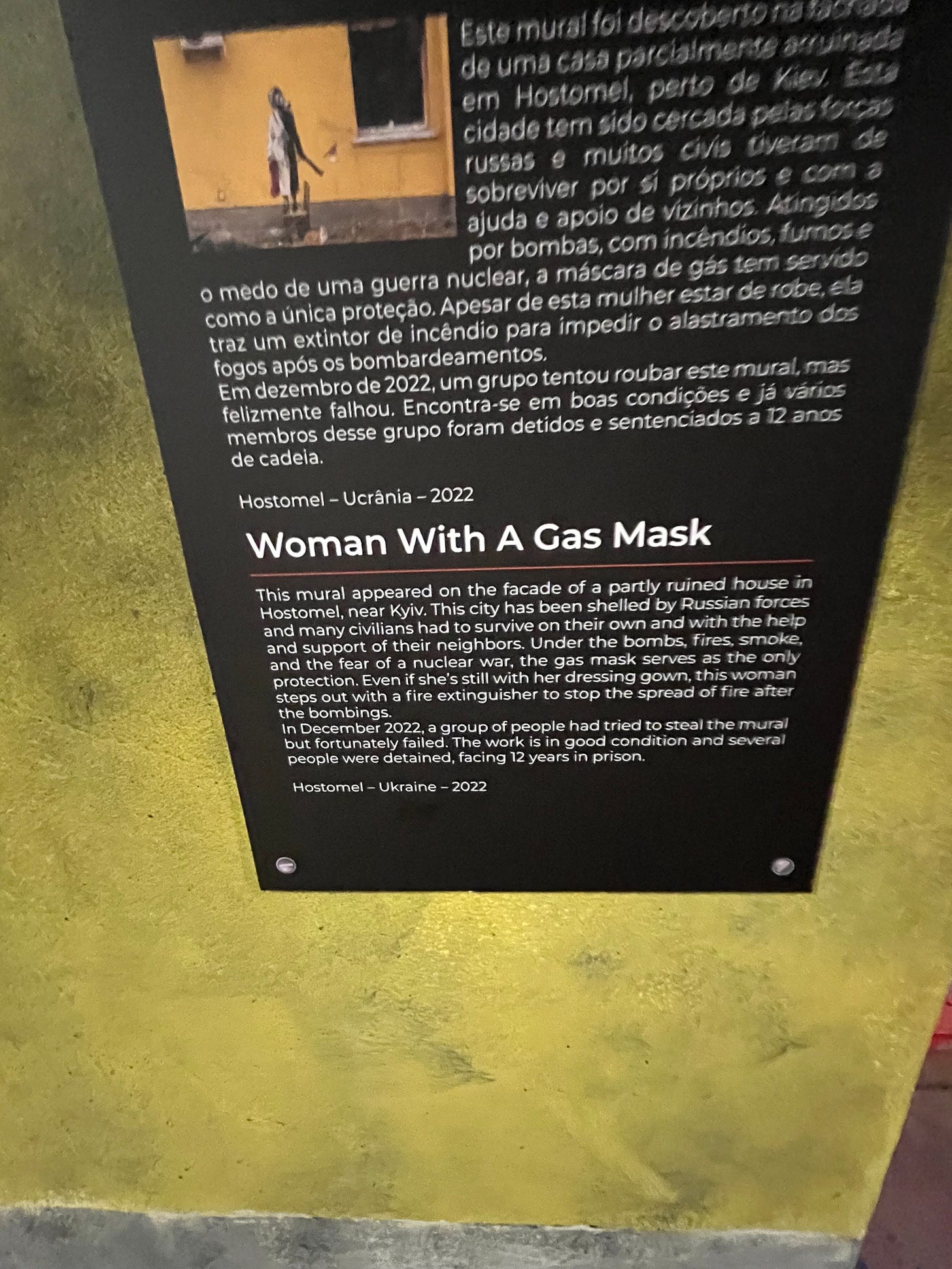

There were plaques to explain the location and context of each piece that was reproduced, as you can see below, but the depth of the discussion was laughable.

When I saw the reproduction above of a Banksy’s satirical homage to Basquiat’s work, I groaned audibly. I had to think about why this particular piece disturbed me so much, especially in relation to the discomfort I had about the whole museum and its intentions.

I may have told the story of Jean-Michel Basquiat being discovered by the Italian dealer, Annina Nosei in a previous post, but I’ll share a bit of it again. I did not know this late artist personally. He was in a NYC artist cluster adjacent to mine, a few years younger, doing street graffiti that was both defiant and playful. He’d been arrested a few times. My activist artist cohort (via PAD/D, Carnival Knowledge, and Not Funny Enough) seemed tame in comparison to his exploits. Our transgressive work included wheat pasting street posters that satirized gentrification and designing interactive games for “carnivals”to educate around reproductive rights. Our work was either censored from exhibitions, ripped down, or covered up by more aggressive artists or ad campaigns. No arrests are part of my memory. We respected, but were also a bit mystified by SAMO’s (Basquiat’s tag name, shared with Al Diaz for a time) interventionist volume.

In 1982, one of my artist peers felt it was time for me to find an art dealer to market my work. I was very ambivalent about this, given how critical I was about the whole art market, but he spoke to Annina about my work, and she made an appointment to visit me in Brooklyn. I figured it wouldn’t hurt to learn from this experience. She arrived quite late. Full of apologies, in her thick Italian accent, she was bursting with excitement about her visit with Basquiat that morning and told me that she planned to lock him up in the basement with tons of art supplies so that he could produce a show for her. I didn’t know he was painter until that day, and from what she described as her plans for his future, I could see that he would have lot more reasons to be enraged. She turned to the wall where my work was on display and exclaimed enthusiastically, “I’d love to give you a show if you could just make your paintings bigger, 6 by 10 feet or larger. I can’t pay my rent with small works.” I sighed and thought I’m not making work to pay her rent nor could I afford to. I thought, she feels like she can order her artists to make things in different sizes like she’s at a shoe store. I thanked her for her time and sent her on her way.

I felt badly for Basquiat being imprisoned to pay her rent. Obviously, he paid a high price to enter that version of the art market. His meteoric rise to celebrity status, accompanied by fancy parties and intense drug use, indicated to many of us that fame was not the path we wanted to follow.

It’s clear that Banksy had some empathy for Basquiat, both as an artist and the way he was fetishized post-death. If we look at the horrible reproduction above, we can see that the museum’s hired artist who copied Banksy’s version of Basquiat (perhaps inspired by this Banksy intervention in 2017) had no clue about what Basquiat was saying or what Banksy was offering as a mockery of the Barbican retrospective in 2017.

Finally, I want to close with images as evidence of the explicit and unashamed exploitation of Banksy’s alluring imagery. The Banksy store was so jam-packed with souvenirs for the wanting-to-be politically correct tourist that I had to leave before I started throwing things on the floor. I needed to channel Reverend Billy’s oratory to “stop shopping.”

It’s fitting that one of the last reproductions that I photographed (see the framed print above) had the following text in the center of an image of an art auction: “I can’t believe that you morons actually buy this shit.” That phrase is both very familiar (although “morons” was not the term I used) and fitting as an end note to this provocative museum experience. Back in 1982, the same year that I debated whether taking my work into the realm of the art dealers was going to be my path, I created a series of stickers called “Stick It: Ra-decals for the Angry Consumer.” Not pictured here is the sticker that said, “I can’t believe people buy this stuff.” People who bought these stickers used them in department stores, supermarkets, and on the ads in the subway stations.

Yes, capitalism will devour everything including our satirical sacred cows and our disobedient artists. We must dismantle this brutal economic system or the ecocide/genocide we are currently witnessing will continue to wreak havoc until there is no one left to read these words. Many deep ecologists and doomers might exclaim that the planet will better off without us, but I’m not sure. New research, both archaeological and historical, suggests that humans have had less harmful relationships with each other and the natural world before capitalism and industrialization came along.

I’m not suggesting that we go back to Paleolithic-style living. That’s romantic folly, and there’s evidence that the appropriation of a so-called primitive lifestyle is not the path that will get humans out of the mess we’re in. Instead, my recipe includes forming affinity groups to strengthen our critical thinking skills and somatic practices that will better regulate our nervous systems. We also need to process our epigenetic trauma through ritual, song, drumming, nature-based meditation, dance, and feasting. Much of this can happen as disobedient interventions in public spaces and more intimate gatherings where we develop strategies for mutual aid and compassionate dialog across political divides. As future essays will attest to, there are many green shoots pushing through the crumbling asphalt, with new paradigms flowing into being, and that may give us a chance to regenerate a world that uses creative, spiritual, and emotional tools to remediate what’s been damaged, practice restorative justice, make reparations, and weave ourselves back into communities that will thrive.

I don’t think that actions against the Banksy Museum and its materialist goals would be a worthwhile location for organizing, but I did want to use this essay to bring attention to a particularly smarmy example of cultural tourism. There are certainly worse ones, colonial ones, that have done more harm. I’ll leave that discussion for another day.

You always give me some hope to chew on despite my fatalistic bent. "New research, both archaeological and historical, suggests that humans have had less harmful relationships with each other and the natural world before capitalism and industrialization came along." I forget most times how my fellow humans (and I) are not necessarily to blame, we are just slaves for our desires. Thanks buzzing Bee. x

Thank you, a fabulous essay. I just finished a class with Berlin Art Institute about making art beyond capitalism and something we discussed at length is how capitalism appropriates and exploits even those who critique the system.