Last week was the hottest on record globally; this week torrential floods are impacting people (including dear friends) all over the northeast of the USA and a heat dome is landing on others. In light of the escalating climate emergency, it feels a bit absurd to be telling a tale from decades ago. I mean, what really is the point of writing about the early stages of my career and what they mean to me now in the midst of what we’re moving through. Perhaps the theme of many of these Substack postings (what will eventually become a book about the essential medicine provided by creative expression in this threshold time) has become irrelevant. Perhaps it would be better to write about “the great unraveling” (as Joanna Macy referred to this time) and what I’m observing about it from my increasingly tiny window into the world. Despite these concerns, I find more sustenance and meaning emerging from my perspective about “the great turning” - the place where Joanna’s book, Despair and Personal Power in the Nuclear Age, brought me 40 years ago. You can read about “The Great Turning” here. Joanna’s insights have inspired many decades of my creative expression designed to awaken those whose passions and creativity could possibly turn the tide of the current mess. Remembering her work’s impact on me back in 1983, again returns to soothe these current doubts. So with that in mind, I’m plowing ahead, with this historical narrative.

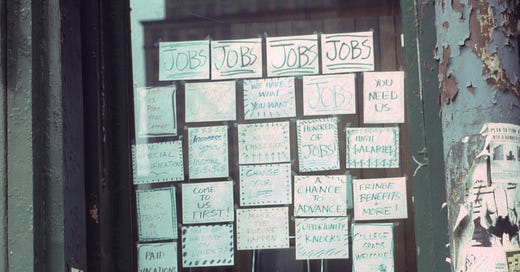

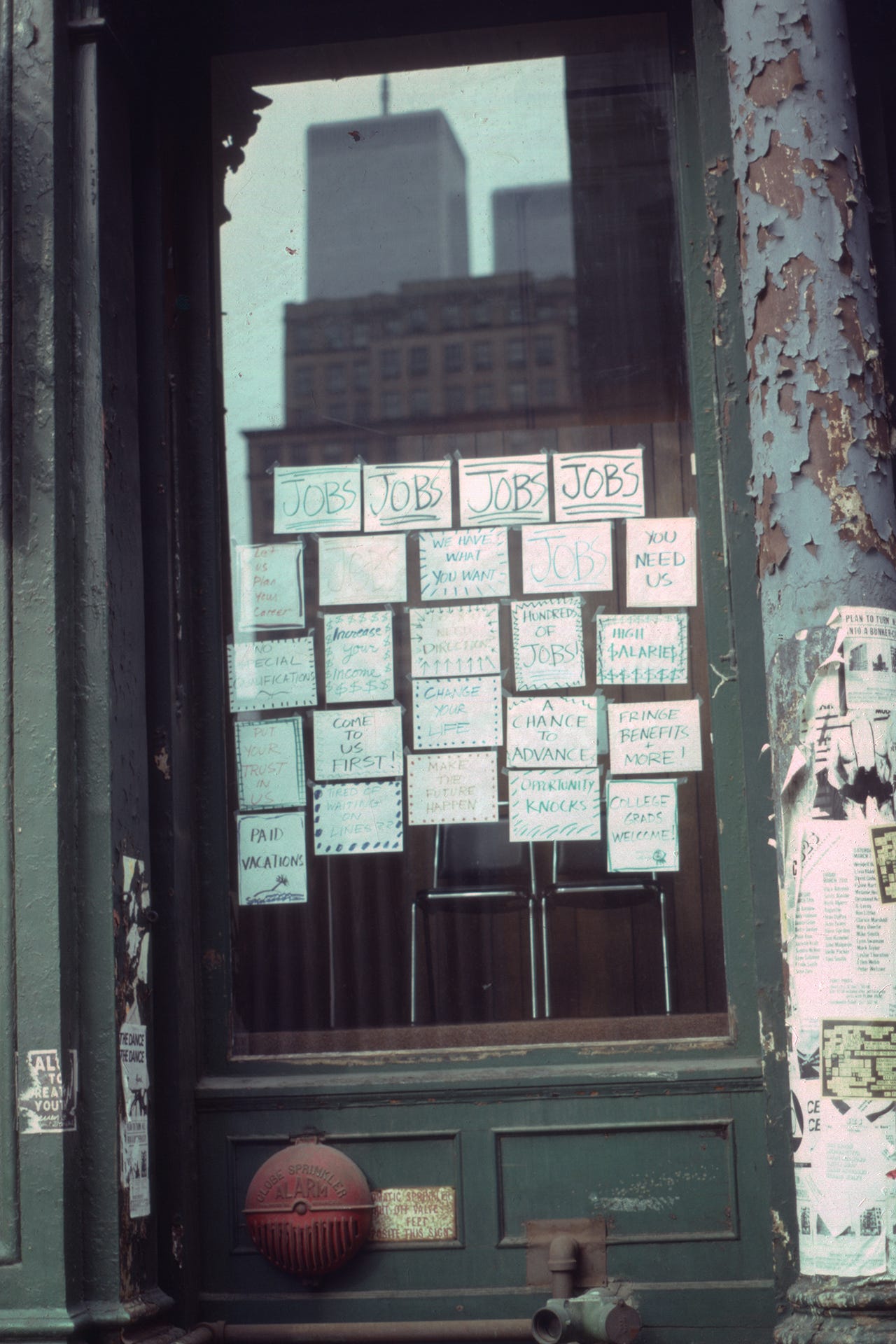

While I was busy getting ready to move to Brooklyn in the spring of 1980, I had a project to mount at the Franklin Furnace. My satirical employment office installation, APPLY WITHIN, transformed the window of the storefront gallery in ways that tempted those folks looking for jobs to enter into the space. I was excited to reach audiences who might never enter a gallery. I was unemployed at the time, so sticking around while folks walked in with their resumes in hand was not a problem. Welcoming them into the space was important to make the experience work.

When visitors sat down on one of the two chairs mounted on a platform in the window, a pressure-sensitive switch turned on the audio loop immediately and visitors were caught in the five minutes of voices reassuring them that they weren’t alone while reminding them that the capitalist system was set up to make them feel like a loser. There was a fair amount of humor in the audio so folks who were brave enough to come into the disguised gallery space were often laughing and feeling held in unexpected ways. Behind the window installation, I created a lounge area for visitors to discuss the challenges they were facing in the labor market and to share their reactions to the piece as a whole. They were able to access a small library of resources that offered other options for labor in our exploitative economic system, while they shared coffee & tea with me.

This project successfully crossed the boundary between audience and gallery while it addressed a relevant social issue, one that I was living inside myself. If someone had told visitors that they had entered a gallery rather than an employment agency, they might have run away before receiving the gift of being seen and heard. In fact, that happened once when I left my post to get coffee and the person minding the store shared with the visitor that this was not a place to get a job, but rather a gallery, and the person left immediately without the reward of being seen in their vulnerability. To take the risk to cross the threshold into the unknown needed a warm welcome.

It’s important to note here that this installation was conceived and mounted long before the terms, “social practice” and “dialogic art” had been written about it or discussed. I was just doing what I felt compelled to do out of a need to find community, and this impulse continues to inform my work to this day.

To see more photos and listen to the audio, go here. https://faculty.washington.edu/bnaidus/APPLY%20WITHIN.html

I received some critical feedback from a couple of elder activist artists who said that my piece was manipulative and exploitative. Both of them were gainfully employed as professors of art and had long ago distanced themselves from the world that I and some audience members were swimming in, so while I understood their perspective, I did not feel it was relevant. Thankfully, the feedback I received from those for whom the project was intended was overwhelmingly positive.

From that point on, I became very interested in creating projects that developed dialog with visitors. I wasn’t the only person who felt excited by this innovative intervention. Lucy R. Lippard happened to be installing a show of political artists’ books in another part of the gallery, and she was impressed by the impact my project was having on gallery visitors. Since she had never heard of me (I was 26 at the time) or my work, she invited me to her loft to learn more. I was both excited and intimidated; after all, I had been reading her writings for years and was a bit starstruck.

I arrived at Lucy’s Prince Street loft with some loose-leaf notebooks filled with photos and texts about my previous installations. After she greeted me, we sat down and talked briefly about my background and the current installation, and she said, “please leave this material with me, and I will decide whether I want to write about it.” As I recall, I felt like I was floating on the vibration of our shared words as I made my way home to Brooklyn.

A month or two later, in the summer of 1980, I opened an issue of ArtForum magazine to discover her article about my work. And then, to my surprise, I found two other short pieces about the project in Art in America and Fuse Magazine.

There was a part of me that was delighted that the work had garnered attention, but I also noticed places of discomfort with this recognition. A part of me felt like I didn’t deserve it (I was too young, too untested, etc.), and thus began years of wrestling off and on with the imposter syndrome. I didn’t have enough self-awareness at the time to understand what I was experiencing, nor did I have a peer group or a counselor with whom I could discuss it. My boyfriend who was struggling with his own career at the time, was not supportive at all. In fact, he became competitive and found many opportunities to put me down. It took two more years, support from a counselor, and a few friends, before I had the courage to end the relationship.

Despite these unpleasant and unexpected side effects from my sudden experience of recognition, as a result of the attention, I was invited to speak on panels and participate in exhibitions, one of which was in London, England at the Institute of Contemporary Art. That show, ISSUE: Social Strategies by Women Arts, was curated by Lippard, and included many artists whose work I had read about, who inspired me in many ways. A few, like me, were just beginning to get recognition. The show included May Stevens, Martha Rosler, Mierle Ukeles Laderman, Adrian Piper, Nancy Spero, Suzanne Lacy & Leslie Labowitz, Bonnie Sherk, Jenny Holzer, Loraine Leeson, Margaret Harrison, and others.

While it was thrill to meet and talk to so many of these artists, it was also challenging to participate when I had so few resources to do so successfully. My airfare was paid for, as well as my hotel room, but there were no funds for food, ground transportation, or materials to make my work on site. During this trip, I learned one of the lessons that many young artists without privilege learn: the attention your work receives may give you opportunities, but without sufficient resources and support, you may underperform, be frustrated, and doubt your abilities.

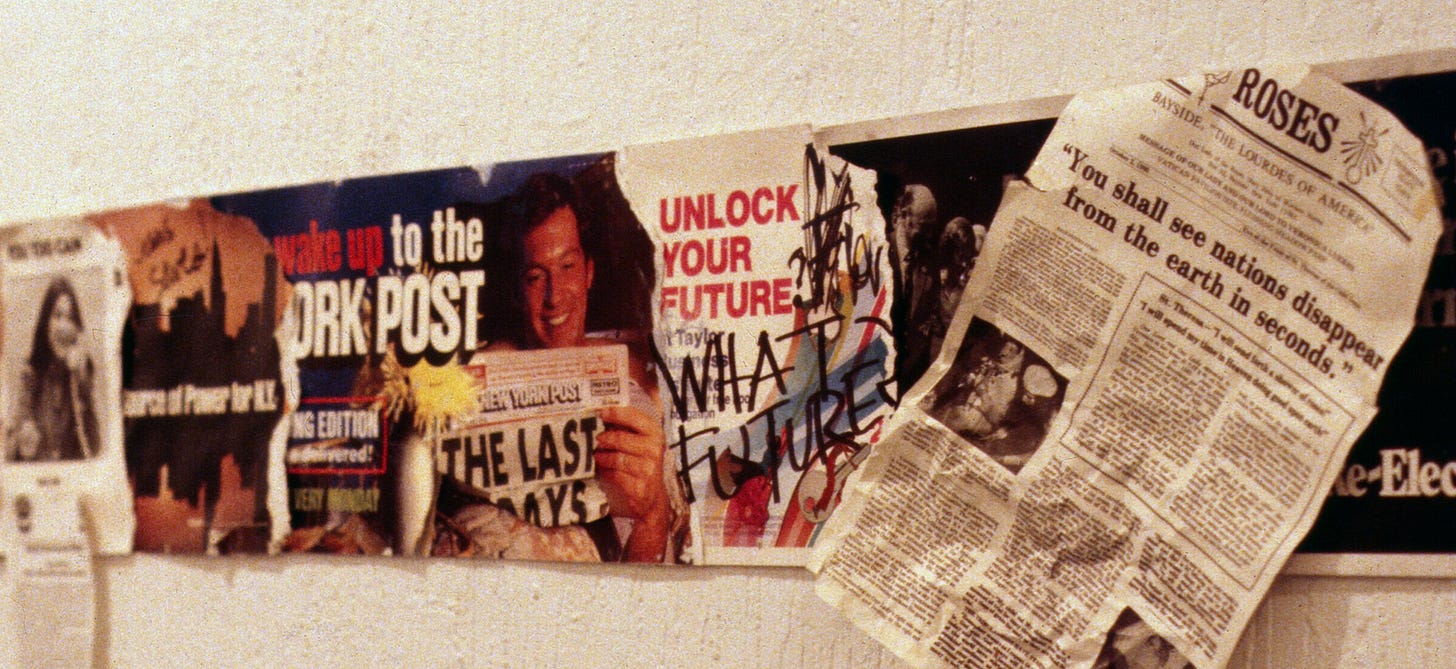

My new audio installation for this London show was called, “The Sky is Falling, The Sky is Falling: A Panacea for Pre-Millenium Tension.” The script for the audio was written in response to the election of Ronald Reagan whose regime’s new policies and legislation unleashed many of the messes we now sit in. Both personal and collective fears shaped the dialog in the audio; those phrases were spliced with advertising excerpts reflecting a mood of panic about the approaching possibility of nuclear apocalypse, the destruction of the social safety net, and the rise of neo-fascism. Audience members heard this tape while filling out petitions that said "We, the undersigned do hereby request to be among the first to go" or "We, the undersigned do hereby request to be among those who survive." Subway posters with graffiti reflecting concerns about a livable future were displayed above the petition table.

Sadly, I was not happy with this project. The concept was decent enough, but the realization did not excite me for a number of reasons. It was created when I was a mess emotionally, smoking too much weed to deal with the latter, and hanging out with a famous jazz pianist who kept me up too late. What ended up being shown at the ICA reflected my ambivalence about showing this kind of work in a gallery rather than creating more public interventions in the street. I felt deeply committed to raising consciousness about the potential for nuclear war, but was this the way to do it? The takeaway for the audience seemed too cynical and not sufficiently proactive. In retrospect, I needed both mentors and collaborators to help strengthen my project and push me to take bigger risks with it, but I did not yet know how to find my cohort.

Another lesson I received from the ICA exhibition came from sharing a hotel room with an artist who was incredibly ambitious to become a big art star (and she did become one). Although I don’t remember much of our conversations, I was able to witness how she worked our hotel room phone every moment she could. She made dates with all the big art world players in London, and whenever she wasn’t sleeping or installing her work, she was out and about, making connections. From my experiences with my soon-to-be ex-boyfriend, I knew that this was probably the biggest part of being successful in the art world, schmoozing with those in power. It all felt so paradoxical to me. Here was an artist with a very definite, progressive, political agenda in her work, playing the game to create a space for her work with the movers and shakers in the high art world. I was confused about this, although I admired the fact that she was stepping into her power as a female artist. I also recognized that I was pretty naïve when it came to understanding the hierarchies of power and the ways that corporate capitalism was enmeshed within the art world. I was about to become more confused as more opportunities presented themselves to me when I returned to NYC.

City Nightmare, ink and pastel on paper, 1981

There was a lot to process when I got home to Brooklyn: I had participated in my first international show with artists I respected, but I felt like a failure because my project had not emerged in the ways that I had hoped for. While it was uplifting to be in this exhibit with artists I admired, there was something that didn’t align right. I knew I wanted to make work that raised consciousness, but I didn’t know how to navigate what appeared to be treacherous waters within the capitalist art market. I had started making installations to avoid the dealing with the marketplace, to be “uncommodifiable,” and to make my content more immediate and dramatic for the viewers, but things were more complicated than I had imagined, as I learned that even transient interventions could be documented and marketed. I wasn’t totally against selling my work, I just wanted control over how it was sold and in what context it would be seen. From my reading, I knew that having that kind of power over one’s work was rare. I realized that I didn’t have sufficient understanding of the terrain I had entered (there were no “how-to” books for emerging activist artists) nor did I have many tools with which to examine the dissonance I was experiencing. So, instead, I threw myself into journaling, swimming at the Y, and biking around Prospect Park, while I ruminated and came up with no conclusions.

Looking back, I really needed to join an activist group working on the issues that concerned me at the time so that I could at least understand the complexity of the issues that my work was exploring, but I didn’t know how to find one.

In my search for more insight, I found some old blank canvases and started painting for the first time in years. I felt very sheepish about sliding back into painting after years of scorning the process. I wasn’t supposed to be making pretty pictures anymore; no more decorations or status objects for the walls of the wealthy. My passion was to make work about the problems we were facing as a species; I didn’t expect a mad rush of buyers looking for those kind of images or interventions and I couldn’t justify being an artist unless it was of service to humanity.

The truth was that I had inadvertently created a bit of an aesthetic straight jacket in grad school thinking that all my work had to fit within a certain container, both in terms of content and form. My projects dealt with personal fears, frustrations, and nightmares that had collective ramifications. I explored the latter through text (either written or recorded inner dialogs, satirical or otherwise) and scavenged materials that suited the content, putting them together in a minimalist design. I still felt it was crucial that my projects were visually compelling enough to seduce the viewers with their appearance (camouflaged or otherwise), but they couldn’t be relying on certain traditions of beauty or refined craft to pull people in.

Now, after many decades of practice, I wonder about the rules I had internalized so that my work would be taken seriously by peers and others. I’m not sure, even now, how much of this was innate (a careful and thoughtful pruning away of what was unnecessary in my practice) or a desire to conform to what was “cutting edge” at the time.

But subversion was also my pattern, so two years after grad school, my instinct to make marks and images was pushing me beyond the tight container I had created. Despite this rebellion, I kept my painting practice mostly private. I invited a few people to see what I was working on, and got some advice and encouragement, but my ambivalence remained steady. Two of the visitors, a couple I knew from my NSCAD years, both up and coming painters (both of whom became “famous”), loved what I was doing, but wanted to know why I was using so little paint. I told them that I liked the “unfinished look” as well as the contrast between opaque and translucent. In truth, I had no money for art supplies given how high my rent was; I was stretching out my paint with turpentine, but I also liked the way it looked. They recommended that I take slides of my work to certain dealers, but I was ambivalent about doing that. This became a repeated theme, peers recommending me to art dealers, that I will explore in a later post.

No Way Out, oil on canvas, 1980, in the collection of Anne Petrocci/Richard Vincek

Looking back at my resumé, relative to where I sit now, I’m amazed by the number of invitations I had to participate in exhibitions and publications during the years I lived in Brooklyn. I was in my late 20s, so I had the energy for all of it. I’m not going to list or detail the content of all the shows and publications here. You can go to my website if that interests you. My intention here is to share how blindsided I was by the sudden and early recognition, and how these experiences eventually shaped a more coherent analysis of what it meant to be a socially engaged artist.

Amassing the critical thinking skills to figure out how to align my career with my ethics was a slow process, partly because the values of the dominant culture and those that I was raised with were in conflict. Some of the concerns I had back then can be asked in a series of straight forward questions (although the answers will likely be complex):

How does one combine a desire for social change with that of success as an artist in our contemporary world?

How do we redefine “success” in relation to a creative practice that is trying to stretch beyond the current paradigm?

What are the contradictions that emerge when needing to make a living in a very corrupt system?

In my next post, I will continue to explore these issues and detail some of the ways that I found as a pathway through the brambles…some of which may have resonance for younger activist artists today and others which have become washed out roads, no longer passable given the economics of this time.