It’s been months since I started writing this post. If you read my post from early May, you’ll know why. I’m returning to the fractured memoir to give my frazzled heart a bit of a break by reassessing a long ago chapter. Perhaps the insights I share about the several intense years I spent in the NYC art world will give readers pause and offer a reappraisal about the benefits and perils of testing oneself in the mainstream art world. Maybe folks reading this will recognize that you don’t necessarily need the fickle ego-stroking found in that world to stand confidently in your creative gifts. It’s a whole different ball of faux glamour since I said “good-bye,” decades ago, to the gritty subway life, so it’s possible that these recollections will feel more nostalgic than instructive. Be that as it may.

I am, as per usual, writing this narrative to deepen my own understanding about the choices I’ve made, but I also hope that stories of my journey will offer a provocation to those who read it. As a participant in a culture undergoing huge shifts, and facing possible extinction, it seems important to remind folks that the gifts and stories you carry can blossom in a myriad of ways, providing unexpected nourishment for others. This is much needed medicine for this time. In other words, you don’t need to go to the BIG CITY to test yourself or become the INFLUENCER of all influencers to make an impact in your neighborhood or community. I’ll write more about the courage and necessity there is to make creative interventions in the latter context in subsequent posts.

Still, without testing myself in the ways I’ll soon describe, I might not be sitting where I am right now, comfortably housed and fed, writing these tales.

I was discussing the content of this chapter with a few of my writer peers at the London Writer’s Salon the other day, and said, “writing about this period feels like ancient history, since it was long before the internet and social media arrived.” We all concurred that it is hard to bring that former world into any coherent focus now - we are all so saturated digitally in ways we could never have imagined then.

The spring of 1980 was multilayered, complex, full of firsts and the stresses of survival: my audio installation about being unemployed went up at the Franklin Furnace (a downtown alternative space that focused on artist’s books, performance art, and installations). It was my first gallery show in NYC, and I was collecting unemployment for the first time. With my housing situation in lower Manhattan becoming untenable, I had moved to downtown Brooklyn, and that was a first as well. I was siphoning some of my rage about the housing crisis into my first street art posters. The heartache of my romantic relationship sent me to my first appointments with a therapist through a mental health program run for artists and creatives with little cash. I will dissect some or all of these firsts through this post, and attempt to give myself and you, my respected readers, a few insights about this intense chapter.

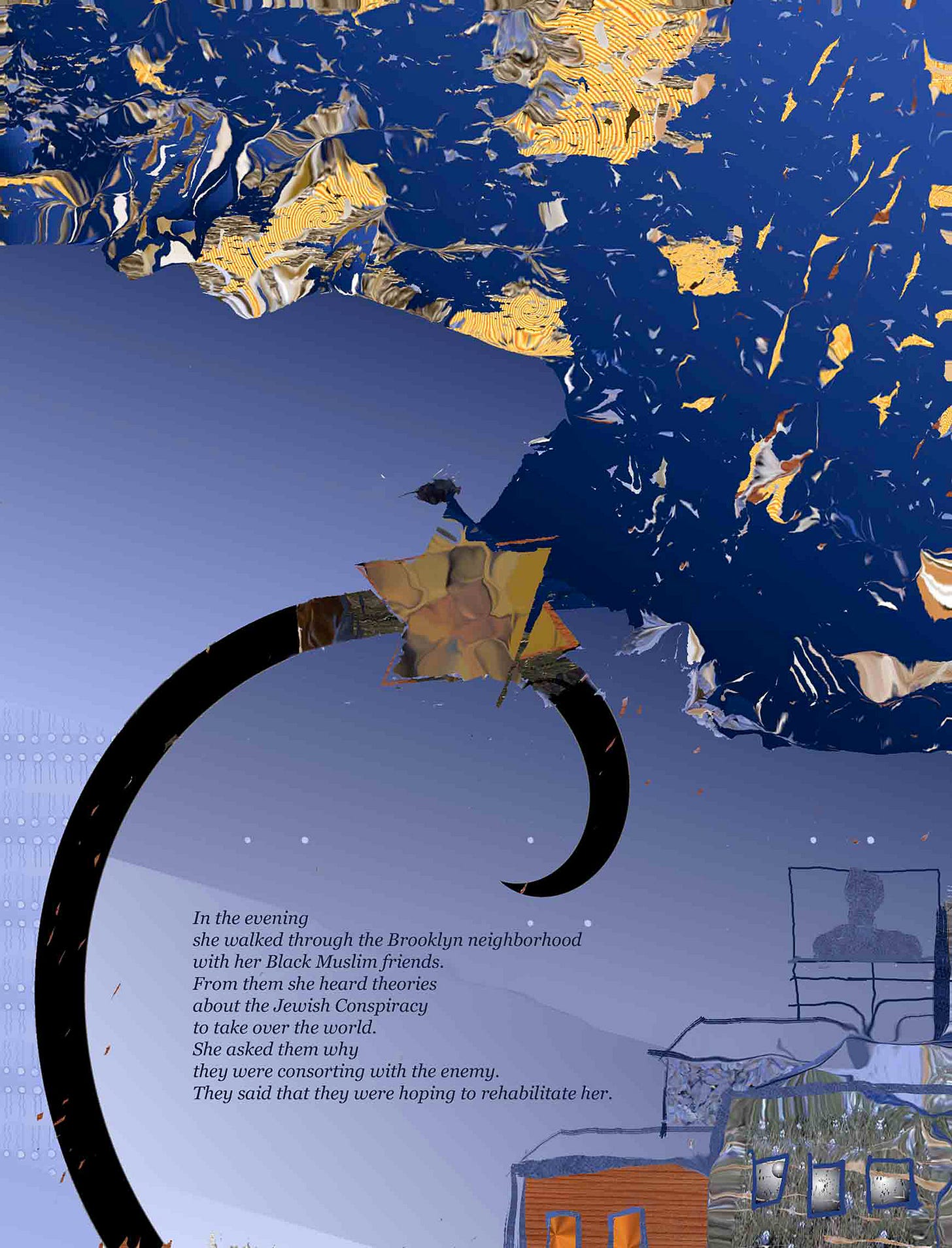

Don’t Cross the Bridge at Night, watercolor, ink, pastel, graphite, 1981

My move to Brooklyn signified the first step in my being liberated from a certain mindset about success; it opened up horizons I hadn’t imagined or considered. My new place in a renovated factory on Atlantic Avenue was just above the roofline of 4-story brownstones in the neighborhood, and occasionally offered views of glorious sunsets. The huge windows blessed the space with lots of light and looked over the roof of a wonderful gospel church. Despite closed windows, the congregants’ voices could be heard serenading the neighborhood with their uplifting songs. Although I had some difficult times while living there, mostly due to my limited resources and challenges with relationships, I was able to create community in some interesting ways.

Soon after moving in, I found a local niche of sorts at the YWCA two blocks away from my front door. As I made my way upstairs to the Y’s locker room, there were vibrant murals and posters on the walls, filled with anti-racist campaigns and quotes from inspiring people of color. I felt embraced by that energy, and knew that I would find a good cohort there.

No Horseplay, Oil on canvas, 1984

Because I was underemployed, my routine became one of swimming a mile a day (88 laps). I slowly made friends with fellow swimmers, other artist “exiles” like the lovely queer shaman-performance artist, Donna Henes. I also found a welcoming group of folks in the sauna where we often had rich conversations about our different cultural experiences, prejudices, and political points of view. A few of us would sometimes walk to the Promenade in Brooklyn Heights through the Arabic section of Atlantic Ave, sharing a joint, joking with each other while discussing the stresses in our lives.

A digital painting from the series, √Other: Breaking Out of the Box, 2001

Moving to Brooklyn may have appeared to be a sign of defeat to some of my artist peers. Many of them expressed a fair amount of bias against living outside of lower Manhattan. I heard comments like, “I guess we won’t be seeing much of you anymore.” I would respond with “it’s just a 10-minute subway ride,” but the sentiment most commonly shared back then was that I was going into exile and that my career would be hampered. Housing south of 14th Street in Manhattan had become increasingly unaffordable (thanks to the real estate investment policies of Mayor Koch’s administration and greedy developers). My downtown Beaver St loft was unlivable for reasons mentioned in a previous post and I needed to move on. Detoxifying from the attitude that living in one place was “cooler” than another was part of my work.

As I have moved around the country, I have observed that this sort of snobbism about certain places being “the happening place” exists everywhere. Without a doubt, some places are more attractive for all sorts of reasons, but having FOMO (fear of missing out) was not going to serve my needs at that time, or truthfully, at any time. And this aversion to Brooklyn back in 1980 is particularly ironic given how many artists flooded Brooklyn in subsequent years. While becoming “cooler,” the arrival of artists with all the businesses and real estate developers in their tail wind, pushed out many longtime residents through the process of gentrification.

As I got to know my new community, I began to notice some of the slow-moving side effects of gentrification. It was deeply troubling to know that local folks were losing their apartments and “mom & pop” businesses were closing due to the greed of landlords. Whole long-standing communities were dispersed by this process, and it pained me to realize then, as it continues to now, that displacement is one of the main ingredients of white supremacy and capitalism.

There was another toxic piece of the piece of the pie that came clearly into view during these years: many policies launched in the Reagan era were causing a disturbing new feature of the landscape. We could see more and more people sleeping outside, sometimes with bags of belongings tucked around them. Many of us living in reclaimed areas were seeing the this phenomena increasing exponentially, and we were informally discussing this in person and on listener sponsored talk shows like WBAI to figure out how to interact with and help the unsheltered.

I recognized that my newly arrived status in Brooklyn was part of what was moving the invasive machine of real estate development - artists and students are typically part of the first wave of the uninvited occupation. I began to make street art about it, and over the next four years displayed it widely. Some of these posters (made crudely with Letraset, peel-off letters, and photocopy machines) were wheat-pasted onto walls in neighborhoods already overwhelmed by the “upscaling” (Soho, TriBeCa); others were posted in areas that seemed on the verge of being taken over (the East Village, Loisaida - aka the Lower East Side, and Park Slope in Brooklyn).

One activist artist organization, PAD/D (Political Art Documentation/Distribution), sponsored a street exhibit about gentrification in the East Village at a key intersection within that neighborhood. As a member of PAD/D, a nascent group started by Lucy R. Lippard, the late Ingrid Sischy, and many others, I was glad to participate, but I also recognized that such efforts had not yet been effective in stopping the process of evicting and displacing folks. Still, it’s important to do this kind of work, at least to raise consciousness about the issues involved, with a few people walking by, if nothing else.

My participation in a group show about real estate issues (Joint Forces, 1982) organized for the Brooklyn Museum started out with an interesting proposal. I asked to be partnered with a housing & tenants’ rights organization in Park Slope and shared my dream to create a satirical real estate agency in their storefront. Both sadly and ironically, when publicity about the museum show was released, the landlord of their building threatened to evict them if my project came to fruition, so I retooled my project into a street poster campaign. It was disappointing not to launch the project Real eSTATE, but it was more important for the organization to keep their space.

But I’m getting ahead of myself - this work about gentrification didn’t emerge until 1982, and 1980 was the year that shifted my whole art career trajectory in some unexpected ways. Before I moved out of Manhattan, I had begun work on a new installation about being underemployed and what it meant to look for work. Thanks to the late Jacki Apple, I was given the opportunity to transform the storefront of the Franklin Furnace into an employment office.

While this is not exactly a cliff hanger, and there’s a part of me that wants to be writing about more immediate concerns, I will continue to explore this narrative, to glean whatever morsels of wisdom can be found in its seams in my next post (almost fully written) “Brooklyn (Part 2).”

Brilliant post!

BRAVA BRAVA as far as I’m concerned this is a bit of a cliff hanger . . .