My two years in grad school and subsequent years in NYC were filled with “names,” many of which will be unfamiliar to folks outside the art world, but to those within it, my narrative may sound a little bit like a name-dropping marathon. Of course, that is not my intention in writing this. I’m continuing to interrogate the complexity of seeking certain forms of success.

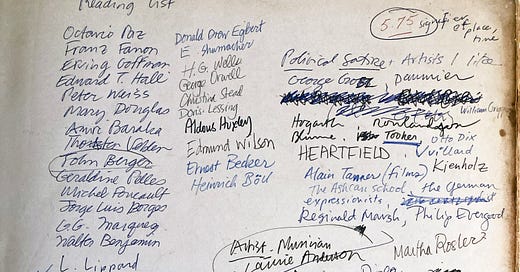

First page of my NSCAD journal, 1976

I applied to a few MFA programs while I was still finishing my senior year in college. In what might seem like a contradiction to my previous anti-elitist attitude, these schools were all Ivy League; I was trying to be pragmatic in relation to the academic market. I wanted to teach, so maybe a big name school would more likely guarantee a position somewhere. I did absolutely no research on who was teaching where or what kinds of theories were influencing the pedagogy of those places. I was applying blind, and I had no contacts at any of the three schools I applied to. Because I had just received a prestigious senior studio art award, it was humbling when I was rejected by all three programs. I licked my wounds briefly, and then immediately made plans to go to NYC and test my luck there while applying for other grad schools.

You may be wondering, why was I so focused on wanting to teach? Even though I’ve written about this countless times in other essays, revisiting this question in this context, may be useful. Briefly, I can say that my experience “studying” with various art teachers was at best frustrating. Some were kind and supportive, and gave me free range, but no sense of what an art practice means in the larger scheme of things. Other teachers emphasized techniques and craft, also without much contextualization. There was an“art for art’s sake” attitude that proliferated, another bit of nasty backlash residue from the McCarthy era. Giving assignments without sharing the historical and theoretical context, or discussing the larger issues surrounding art making, felt alienating and irresponsible. Although I was not able to articulate my concerns fully at age 21, in retrospect, I can say that not discussing certain things in relation to art making like economic class, patriarchy and white supremacy (the impacts of systemic oppression on the culture we had access to and the artists themselves) left a big hole in our understanding of what we were doing. Not broaching discussions about who an artist can be besides being an entertainer, a decorator, or an investment item for the rich, felt neglectful. It took many years of independent reading and discussions with others to remediate what was left out and expand the roles of the artist to include that of healer, ritual leader, provocateur, truth teller, and documenter. I knew instinctively, without knowing all the details, that the teaching of art or the mentoring of future artists could be done differently, and I wanted to learn how to do that. Grad school seemed like the place to figure that out, and tasting a bit of the NY art scene beforehand seemed wise.

When I first moved to NYC to live there full-time, I was not new to the city. I had spent countless weekends there during my childhood and teen years, visiting relatives, and just hanging out with friends. I had had wonderful adventures wandering around the neighborhoods where my parents grew up and thankfully, only a few traumatic experiences (those are not essential to share as part of this story). I knew how to walk, talk, and dress in the city so that I was mostly under the radar (not perceived as a tourist). I also passed as Latina, so I could move through a spectrum of neighborhoods with relative ease, but my gender made me vulnerable, no matter what I was wearing. I often dressed in ways to obscure my curves, thinking that would protect me from the gaze and taunts of male strangers, but I was wrong.

Soon after arriving in the city in the late summer of 1975, I became aware of how crucial my tiny network of former fellow students would be for housing and job possibilities. One connection offered me temporary lodging in a loft in Little Italy on the corner of Mulberry and Broome. It was a great neighborhood in which to begin this next chapter, full of history, exciting smells, and fresh cannoli. A few blocks away was Soho, not yet discovered by mobs of tourists; we visited a few local bars hoping to take in some of the vibrant, bohemian energy emerging from the dark and ominous warehouses. Some windows were glowing with the lights of the recently nested who either built their own fixtures (bathroom, kitchen, lights, etc.) in those former sweat shops or factory spaces or paid a fee for them. Walking through these streets required our vigilance; even though most of the first DIY artist-residents in the area were not well off (rent was cheap back then), there was an occasional mugger or flasher crawling around the shadows. Despite that threat, it felt like we were on the edge of something exciting when the economics of being an artist in NYC seemed doable.

After a couple of months, my roommate and I needed new housing, and some Cooper Union students, Jean Foos & friend, who I’d met at the Provincetown Workshop the previous summer, asked us if we wanted to take over the lease on their tiny, cockroach-infested, tenement apartment, for $200/month. We were thrilled to do so. Located a block north of the East Village, we were able to witness many exciting examples of a city recreating itself: abandoned buildings were being squatted by anarchist collectives and community gardens were sprouting up in empty lots. Around the corner, when we had enough change in our pockets, we could savor some of the cultural cuisine of my heritage at Hammer’s Dairy Restaurant and get affectionately teased by the domineering wait staff. Lively, grass roots art was happening on every block. Tags of the counterculture of that time, mostly punk and hippie aesthetics proliferated on the wheat-pasted flyers that covered almost every public surface, announcing spiritual gatherings, readings, performances, and activism of all sorts, much of it coming from marginalized communities reclaiming their sovereignty.

N, my roommate, got steady work at the Strand Bookstore, sitting at the desk that had previously been occupied by the punk singer & poet, Patti Smith. (Did that make N feel special? Yes, it did.) It was an easy walk from our place, and not infrequently, she brought home stray poets and wild philosophers carrying bottles of wine to eat at our small table. One of them, who later became quite infamous for foisting his weighty manifestos, along with maps of ambitious eco-remediation projects into the hands of unwary conceptual artists, worked at the Fulton Fish Market. He would occasionally bring a big, raw fish for me to cook up and provoke discussions that would take us deep into art and politics, causing us to argue late into the night.

Aside from this exciting beginning to our social world, work life was a strange mix of things. I had a few regular cleaning gigs for artists who I’d met in P’town, but I knew I wouldn’t last in that line of work (I wasn’t very good at it). I began searching in the “classified” section of the Village Voice under the heading “ARTIST” (lol). A position working in an art slide company looked intriguing. My interview was with a very grizzled, wary-looking, old man in a rabbit warren of offices filled with surveillance cameras, copy stands, and art books. His demeanor was not charming; he reminded me of a psychopath in a Hollywood film I would likely avoid watching, but I decided to give him the benefit of the doubt. I needed an income. His claim that all of their slides were taken from the actual art itself was dubious given the piles of art books in every room. A co-worker confirmed my suspicions and recommended that I find another place of employment. On my third day at work, the boss sent me into a room filled with slides strewn all over the floor (thousands of them, up to the tops of my shoes) and asked me organize it. My coworker told me that a previous employee had had a fit, and thrown shelves of slides on the floor as a parting gesture. I had not signed up to spin straw into gold, and immediately gave my notice, walking out the door at lunch never to return.

A week later, I found a much nicer environment, working under the gentle stewardship of two white, gay men, at a stencil art factory. I did product design for minimum wage - $3.25/hour) for about 30 hours a week. With that kind of income, it was clear that applying to grad school needed to be my next step.

The question was where to apply, especially given that I would receive no financial support from my parents for this dive into impracticality. I took my time to find three more appropriate MFA programs, and reflected on the following recommendation before sending in applications.

During a school break in the winter of 1973-74, I had visited my brother in San Francisco with my dear late friend, Michael Oshima. The two of us were eager to explore San Francisco (our first visit) and had intentions to move there for grad school. We had been studying with a British conceptual sculptor, Andrew Leicester, at Carleton, and after reading Lucy R. Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972, we had become passionate about conceptual art. So when we discovered that there was a Museum of Conceptual Art in the Mission, we were eager to stop by. The former director of MoCA, Tom Marioni, invited us to sit on his couch and offered us Anchor Steam beers from the fridge. The only other furniture in this empty warehouse space was a long table covered with looseleaf notebooks, filled with documentation of previous performances and installations. We told him of our desire to study at the San Francisco Art Institute, and he strongly discouraged us, saying that we should avoid all of the California MFA programs. This conversation depressed us because we had imagined that the Bay Area was the most cutting edge, cultural hub for art, revolution, queer liberation, and feminism. Tom assured us that the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design was the only place where we would get the inspiration needed to become the artists we wanted to be. Michael decided to go there for the summer school session. Although he had mixed reviews about the experience, I decided to apply to NSCAD and to two other schools.

After passing the written application hurdle, I was flown to Halifax for an in-person interview, all expenses paid. The visiting artist apartment where I was lodged felt like a luxury hotel compared to our tiny NYC apartment. I had no idea what I was getting into, but there was something very seductive about this unfamiliar culture in this stark Canadian port city, filled with merchant marines and container ships.

My interview with the director of the graduate program, the late Robert Berlind, a very eloquent and gentle soul, offered me some insight into why my application had risen to the top of the pile. He had edited my slides to find the ones that would bring the most excitement to the selection committee. To this day, I’m not skilled at how to select a compelling mix of images to use in applications, so I was grateful for his unsolicited help. Given how low my self-esteem was at the time, I was amazed that I had made the cut.

A very poor slide scan of a tiny acrylic painting (maybe 5”x8”) created on the floor of my bedroom/living room on East 15th Street. It wowed the admissions committee at NSCAD because they thought it was much, much bigger.

In that era (1970s), NSCAD was essentially an auxiliary hub of the contemporary art world’s avant-garde. Pierre Trudeau, the Prime Minister of Canada at the time, had funneled tons of money into the Atlantic Provinces to uplift their economy, and NSCAD was one of their beneficiaries. The school opened a publishing house to lift up the work of various conceptual, minimalist, and performance artists, and many faculty had come from places like CalArts. It was an experiment in cultural imperialism, designed to shift the local aesthetic from painted seascapes of Peggy’s Cove to the heady interventions of Joseph Beuys. And as a beneficiary of these resources, I was offered a free MFA, with a teaching fellowship that paid for my living expenses, supplies, and tuition. To learn more about the heyday of NSCAD, the school’s first president, the late Gary Neill Kennedy, wrote a book about it called: The Last Art College, chronicling the years, 1967-78 (the last two were during my time there). I haven’t read the book, but several reviews indicated that there are some distortions. Once I get it from the library, I’ll see where it lands in relation to my experience.

Life at NSCAD was not easy for me. I struggled with many things: being the only woman in my class and the only American provided some interesting challenges. I had also been accepted into the program as the only painter because a few of the faculty had decided that they were done with their conceptual (“dematerialized”) phase and were returning to painting. Not long after I moved into my shared studio, I was taken to task for continuing to paint by my studio mate (Bruce Barber, then a Marxist performance artist) who impressed me with his intellect. He said that painting was anachronistic, a bourgeois activity, and asked me why I wanted to make commodities to decorate the walls of the rich. He exposed me to the writings of cultural & political thinkers like John Berger, Paolo Freire, Ivan Illich, and many others. I was only 23, curious, eager to learn, and open to all of his suggestions.

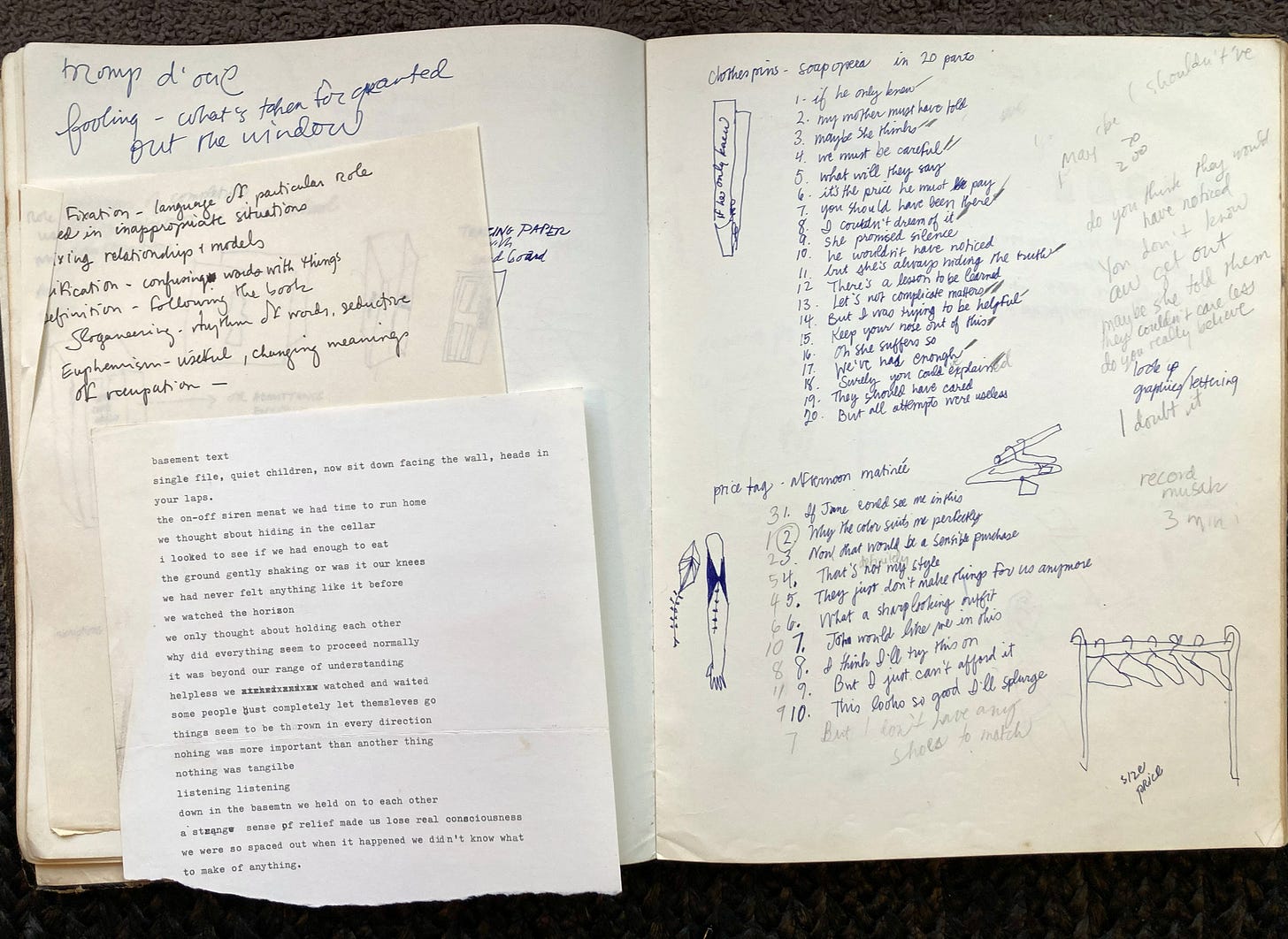

As my critical thinking expanded, I questioned everything I had been doing. I started hauling scavenged materials up to our studio, scribbling on torn bits of paper, pinning them on the wall, with lines of text. I designed memory maps, wrote wild rants on my old typewriter, journaled my dreams, and took lots of photos. I learned how to use a port-a-pack (making videos required a suitcase back then and editing involved the use of a grease pencil) and created plans for installations. I continued to draw, but my paints & brushes began life in a box for the rest of my time in Halifax.

Journaling texts for audios - Summer 1977

At graduate seminars, I occasionally was asked, “and how does the female in the room feel about this?” I had been let in the gate, but they weren’t going to make it easy for me. I was beginning to articulate more fully my relation to feminism through a variety of pieces about the ways women were girdled (literally and metaphorically) by bourgeois propriety, but there was not much written yet about feminist art. Lucy Lippard’s new book, From the Center, seemed to highlight an essentialism popular in early feminist art; the early definitions of what was feminist art and what wasn’t, did not feel liberating. My critique was noted by the male faculty and they decided that we had arrived at a “post-feminist moment.” They were obnoxiously giddy with what that implied, and shared with me that it was time to invite a bunch of female curators, gallerists, and artists to speak on campus. Although I was glad to have more women’s voices in the mix, I was disturbed by their interpretation of my critique.

My first semester in the program, I was the teaching assistant for the only female on the faculty, Mira Schor, (now a well-known painter, respected educator and writer, and still a friend of mine) and saw how skillfully she was able to navigate the micro-aggressions of her colleagues, but I knew it was taking a toll, given my own experiences. Being in a minority that is either ignored or provoked for being different can make one doubt one’s strengths and cause deep suffering. I wasn’t yet ready to make much art about this topic, but I was journaling so it could feed future work. In the meantime, I tried to build alliances with queer, female, and students of color, undergraduates who were struggling, too. In my first attempt to deprogram myself from internalized patriarchy, I built my first installation, Hanging Up( some laundry), that dealt with some of the frustrations I was experiencing about living in a female body in a sexist world. Inspired by Duchamp’s “readymades” I assembled many found objects with text that spoke to feelings of restriction and shame. A center piece of the installation was a small sketch: “The wrong day to wear white pants” that caused quite a stir and the sharing of many stories.

Very first personal announcement cards of my art career. This lone remnant has been abused by time, poor storage and stains from rubber cement, but it gives you a sense of my changing aesthetic.

In reading reviews of The Last Art School, I learned that the history of sexism at NSCAD had some extraordinary moments. Lucy R. Lippard and several others had sent a telegram to the school’s president in response to the all-male roster at the Halifax Conference of 1970, a confluence of conceptual artists and their cohort, and somehow this telegram shook the powers that be sufficiently to open their doors a tiny bit wider. Unfortunately, it wasn’t until long after I left the program that there was more consciousness about gender representation, not just tokenism, for other excluded groups as well.

NSCAD had the funds to bring in visiting international artists, writers, curators, and cultural critics to give public talks on a weekly basis, and many of those visitors would come to our studios, if invited. Outside of the competitive energy of NYC and elsewhere, they could let down their guard and make deeper connections with us.

One of the visiting performance artists, Laurie Anderson, who took a liking to my explorations with text encouraged me to record my words, so with her support, we went into the sound room and I learned how to make a 4-track audio loop with eery sound effects. That loop we created played inside the first iterations of my installation about nuclear nightmares (THIS IS NOT A TEST). A later version was featured in many exhibitions for the next 10 years. Laurie went on to become a major art & pop music star, and although I did not keep in touch with her, our interaction and her story-telling work nourished my own work for many years to come.

THIS IS NOT A TEST, audio installation, Anna Leonowens Gallery Basement, 1978 - it was reconfigured multiple times and exhibited in many places including the New York Coliseum in a show organized by the NY Feminist Art Institute, then in The End of the World show at the New Museum of Contemporary Art, and several university and college galleries across the country up until 1992.

Occasionally, a visitor to the studio, like Donald Kuspit, an art critic from the NY Times, would implore me to NOT give up painting, saying that installations will go out of fashion soon enough, and that I had the potential to be a great painter. One advisor, an outspoken feminist performance artist, the late Ann Wilson, wanted to lock me in a cabin in the woods with paints, brushes and canvases, but I just laughed. I told her that I was not going to make precious objects for the wealthy. I naïvely thought that my installations, filled with sounds, words, and scavenged materials, could not be commodified. I didn’t realize then that even the most ephemeral can be documented and hence marketed and purchased.

My first year advisor, Gerald Ferguson, who I had to plead to work with me upon arrival (the admissions committee hadn’t thought that far ahead) had gotten frustrated with me (and I with him) after months of trying to be in a decent dialog with one another. He invited Ree Morton from Chicago to come work with me the following year, and I was really excited by that possibility. Her work had deeply intrigued me after seeing it reproduced and discussed in From the Center. Tragically, she died in a car accident soon after receiving and accepting the invitation. It was a huge loss, and the artists who took her place: two sweet dancer/choreographers who worked with Robert Wilson, the late Andy deGroot and James Reigenborn, Ann Wilson, and the late Vito Acconci, could not replace her. I mourned her deeply without ever knowing her.

One of the things that helped me emerge from that grief as well as all the inner conflicts about what to make and for whom, was the discovery of the book, Teaching as a Subversive Activity by Neil Postman and Charles Weingartner. I’d been interested in alternative education for years since I’d first read Paul Goodman & writings about Summerhill. I recognized that the dominant pedagogical paradigm we were swimming inside was not raising consciousness, questioning the status quo, or offering possibilities for something different. This book gave me some strategies that seemed easily adaptable to teaching art in an interdisciplinary way. As I was beginning to digest the content, I offered a seminar talk about alternative ways to teach art, as well as alternative ways to be an artist (rejecting the conventional art world path). It raised lots of questions, particularly for those in the room who seemed to be accepting the standard pathways, but for me, it increased my confidence in a teaching career.

I was invited to teach a course on my own, right after graduating with my MFA during the summer session. I used a subversive exercise from the book to guide the class. We looked at words with complex connotations such as the word, exotic, and students would make an art piece in any medium to investigate these loaded words, with many implications about power, class, and so on. I saw how teaching art could enhance critical thinking and it has informed my teaching practice ever since.

There were many paradoxes to navigate as I danced deeper into the muck of what makes some art valued and other art, not so much. I witnessed intense wars of white male egos in public discussions, and several occasions where opportunism was the main ingredient in social exchanges. I had advisors who gaslit me, gave me poor advice (you should be making films not videos), accused me of being arrogant (any assertive woman could be perceived that way), and some who tried to exploit my imagination for their own projects (one big name I won’t mention, a late public & performance artist who was particularly manipulative in that way).

I could have become very cynical, but I was saved by the women artists, writers, and curators who offered various kinds of support during my last year at NSCAD. Their stories reinforced my understanding of art as a healing tool, as a way to create community, and envision a different world. Many of those women (Martha Wilson, the late Jacki Apple, and Helene Winer, to name a few) opened doors for me when I went back to NYC, both metaphorical ones and literal ones, and without them I would not have had my first show in an alternative space, my first jobs at NYSCA, the Franklin Furnace, Printed Matter, Artist’s Space, and so on. The sisterhood essentially fed me and gave me a career. So herein lies one of the contradictions that I want to explore. Artists who intend to be subversive in a capitalist society, by confronting patriarchy, for example, can get easily subsumed within the system….just because we have rent to pay.

Another paradox of my personal dive into social engaged work was that I living in Canada at a time of intense nationalism (in response to US domination) and for the Quebecois, in response to English-speaking domination. The First Nations were making their stories of oppression more visible and the local Black community who arrived in Halifax’s twin city, Dartmouth, over a hundred years ago, as a final stop on the underground railroad, were speaking more openly about injustices, and, yet, none of this content made its way into my work. I observed these tensions and conflicts, but my outsider status gave me no authority to speak about them nor did I have the tools yet to do community-based work. Given that my first advisor was painting grids and dots, it’s amazing that I found my way to making work that spoke to my fears, dreams, and concerns.

Probably the most dynamic aspect of that time were all the liberation movements emerging from so many parts of society; that energy was potent for those paying attention. It catalyzed my imagination in many conscious and unconscious ways, but it raised dilemmas about where to put the art, who was this art being made for, what was its purpose, and what was its impact.

This post may offer more questions than answers about what it means to question the standard pathways to success in the mainstream art world, but I want to close with some thoughts about the contradictions that are still so palpable in the present moment.

Many people think of the The Guerilla Girls as an example of radical artists taking on the powers that run the mainstream art world. I know the founders of that group well. One of them was part of a feminist art support group that we co-organized called Not Funny Enough, a precursor of GG. The Guerilla Girls are a good example of liberal feminism. One of their goals was to get more women’s art into museums and galleries, by calling out the lack of representation and sexism that was so evident; a solid intention with a seemingly worthy outcome. Yet, I never heard them question what entry into those institutions actually means despite their feisty, transgressive stance. Once you have been offered a slice of the rotten pie, a prize you’ve been seeking for most of your career, what are the chances that you will spit it out or try to bake a new one? This issue continues to raise questions today. What does it mean when wonderfully subversive artists of color, queer artists, and other artist members of marginalized groups, finally get their day in the sun with museum retrospectives and solo shows at blue chip galleries? We can applaud their “success,” but need to be cautious about what it represents. Capitalism can consume us with its promises of riches, prestige, and security, but there’s a shadow side and a shallow side that may not be apparent to many. Our work continues to be one of finding strategies to bake a new pie. When I was at NSCAD, I didn’t have a clue about how to do the latter, but I was going to try to visualize it, at the very least.

In my last months in Halifax, I unexpectedly became involved with a very ambitious artist who had already made his mark in his home country. He had grown up within the intelligentsia class, and had a confidence, brilliance, and defiance that impressed me. He offered me resources (books to read and ideas to ponder) that I found deeply attractive. We had a very romantic, intellectually rich, but very complicated relationship for over four years, and in fact, became engaged during part of that time. Over time, I recognized that his overwhelming drivenness emerged from deep and complex psychological wounds from his early life and adulthood. Although he saw himself as mentoring me into the world of high art (how to dress, who to meet, and where to show up), I actually learned more about how I did not want to be an artist. If he didn’t see his name in print, he wasn’t doing enough to get the right connections. Despite the fact that he created very compelling and powerful art, he seemed at times to be more obsessed with recognition and climbing the success ladder than making the work itself. When my work started getting recognition in a time when his wasn’t, he became intensely competitive rather than supportive, and this drove one of the major wedges in our ability to stay together. Despite our difficulties, our time together was very instructional. It taught me who I wanted to be and with whom I wanted to be. From afar, I’ve witnessed his ambitions flower into the version of success he was aiming for and have heard his former students (many of whom do powerful political art) rave about his influence. I’m glad for him, and grateful for what I learned from him, but don’t feel compelled to share his name at the moment. I’m gifting myself with this privacy.

As you will learn in my next post, I did participate in the NY art world in a variety of ways. I went through the doors that opened for me via the networks that were created in grad school. I ended up being in the right place, at the right time, with the right thing, getting recognition and many invitations to be in shows in museums and alternative spaces. As I became more conscious of how my values came into conflict with what I was being invited into, I began to plot my escape. More about those adventures in my next posts.

I can relate in so many ways Beverly! Appreciate all you wrote here and that you share it so freely.

I find this fascinating and thought provoking. Very different from my 1990s science graduate studies. These seem tame in comparison especially about the effects of our research on the wider world, where science seems to have little intellectual curiosity. Thanks.