Being Programmed

for Certain Ideas about Success

In order to interrogate my own programming, I need to take you on a very abbreviated journey into the ways I internalized certain values, learned new ones and rejected others. Please know that I know that I am speaking from a place of intersecting privileges, and recognize the complexity of what I’m addressing.

The list of instructions below makes me want to gag as I read it for the umpteenth time. Does it sound familiar to you?

Be a good student, get good grades, compete for whatever is offered that might help you get points or skills for future endeavors, do the extra-curricular activities that can help get you into a good college, be responsible, do not cause trouble, be well liked, hang out with the right people, win awards, go to college, study something that guarantees a respectable profession that provides sufficient income for essential material needs and then some for the family you will have, and in your copious free time, do good deeds for others: your family, your community, and the world.

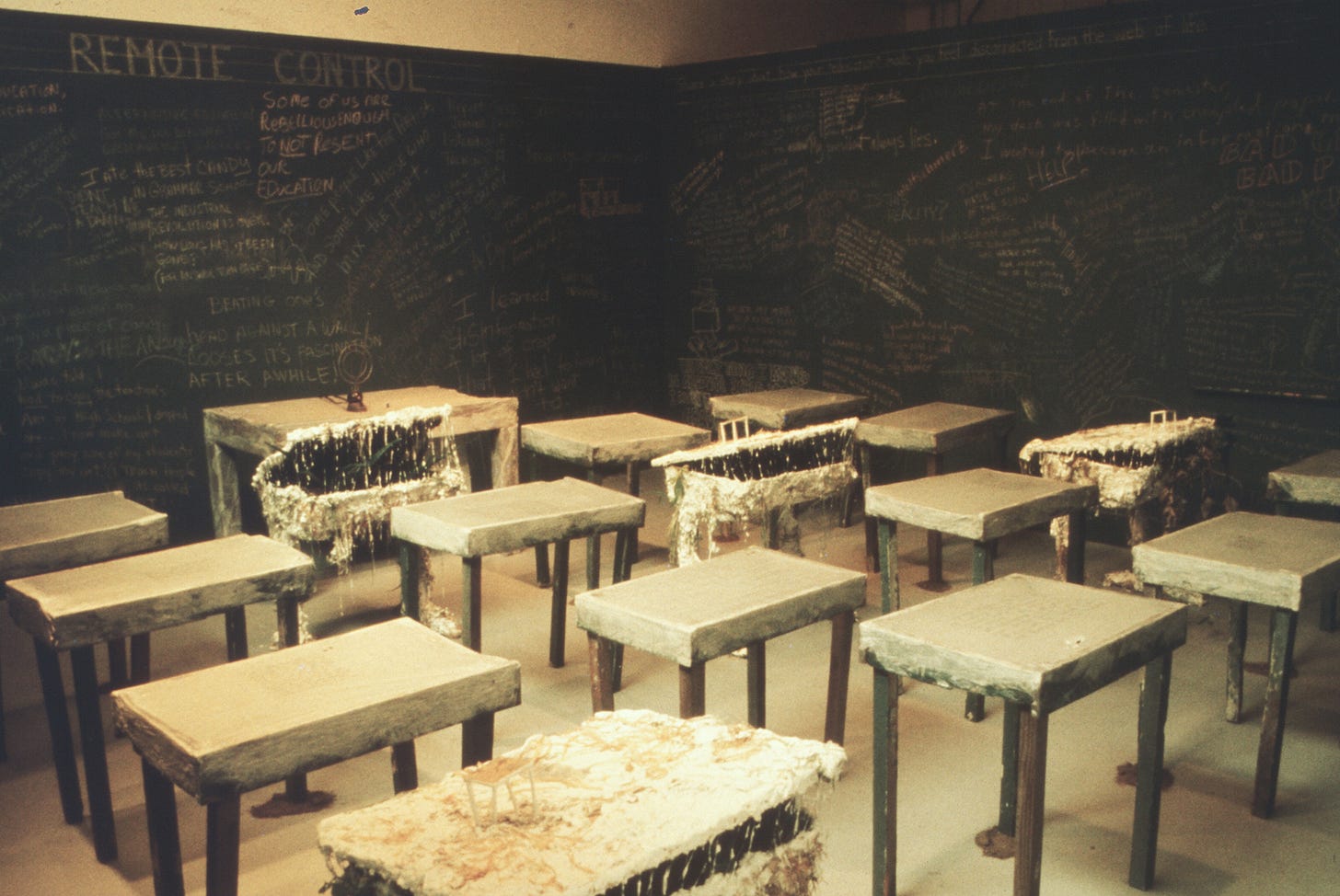

Remote Control, audience-participatory/audio installation, 1991, Orange County Center for Contemporary Art (CA)

There are many nuances that could be added to this list depending on the emotional landscape living within your parents, the layers of oppression that have visited your family, or the generation you were born into. And if one is female-bodied or from a marginalized group of any kind, there are more specifications added to this list that included various amounts of policing of your gender presentation and a strong dose of caution when it comes to taking risks of any kind.

Despite growing up with few t.v. channels, books or magazines in the house, and restrictions (or sustained frowns) about what and how much media did come into our house (NO Laurel & Hardy, Three Stooges, James Bond, or comic books), somehow a few layers of dominant culture’s programming took hold. Increasingly glossy ads gave us an endless diet of seductive messages about who we should be, what we should look like, where and how we should live, if we just bought the right products and played our cards right. And, of course, in recent years, with the social media whirlwind, its influencers and algorithms, this onslaught has only intensified.

Consumerist propaganda has been incredibly successful, responding to both epigenetic wounds of scarcity, inadequacy, and so much more. Combine that with early training in survival of the fittest ideology, found in winner-takes-all games like musical chairs, perhaps it’s no surprise that the ruthlessly competitive culture of the so-called “developed world” has taken us to this ecocidal edge.

There was not much that drew me into a conventional vision of success. I only saw alienation there. Factors that contributed to my rebellion were many, including the cognitive dissonance of not fitting in, not wanting to fit in, and in the many kinds of hypocrisy lurking within the facade of the Amerikkkan dream. My refusal to stand and say the pledge of allegiance while still in elementary school was just one indicator that I was not interested in conforming to the status quo.

I was also being raised outside of religious institutions. Instead museums and libraries became my sacred spaces. Free, deeply serene, and filled with brilliance. There you could transcend everyday life and be transformed by beauty and truth. Ah, for the innocence of youth!!!

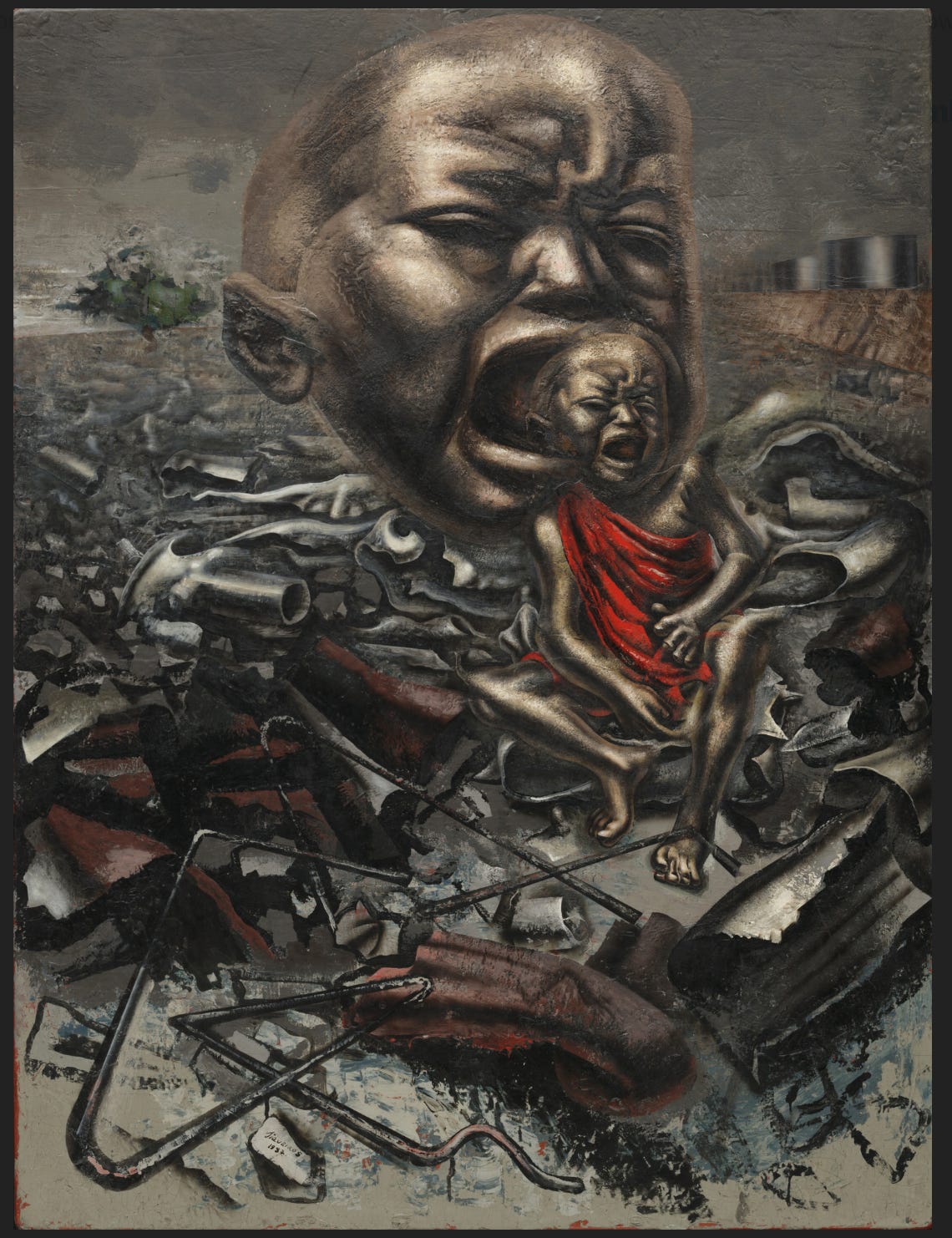

My parents started taking me to museums very early in my life, mostly in NYC (they were free back then). I didn’t question the authority of what was on the walls or the “genius” of these artists. It also didn’t register that the artists were almost all men, and mostly white. Interestingly enough, the first painting that totally captivated me, was “The Echo of a Scream” by David Alfaro Siquieros. This was one of the few paintings in the collection (back in the 1960s) by an artist of color. I sometimes sat with the image of the HUGE screaming baby head (and it’s smaller version) for a long time, while my parents wandered elsewhere knowing I was mesmerized and would not move from the bench. I saw myself in the painting, surrounded by the garbage of modern civilization. It felt like a deep affirmation of the feelings I’d been having. The person who painted this had visited my world and was unafraid of sharing what he’d seen. I didn’t realize that there was a tree in the background (left side) until I was much older. The one ray of hope in the landscape had been obscured up until then, but it emerged in my consciousness at just the right time.

David Alfaro Siquieros, Echo of a Scream, 1937

My encounter with this painting has lasted a lifetime, although it’s been many years since I’ve seen it in person. It taught me not to be afraid of depicting the difficult things in life and to be fully present to whatever wants to emerge from my fingers, no matter what the form. What the painting did NOT teach me was how it arrived on the wall of a museum. To my child’s mind, it seemed like something magical had lifted this artist’s work out of the many oceans of artwork in the world, and due to the unquestioned genius of the artist, it had been placed in the collection to be protected forever.

Many questions about the context of art began to percolate with greater intensity once I decided to major in studio art and went on for an MFA. How does a museum decide what art is valuable enough to put on display? Who are the ones who decide what is good art and what isn’t? How do these values shift depending on the historical context? What are the gates that an artist has to pass through in order for their work to arrive on a museum wall?

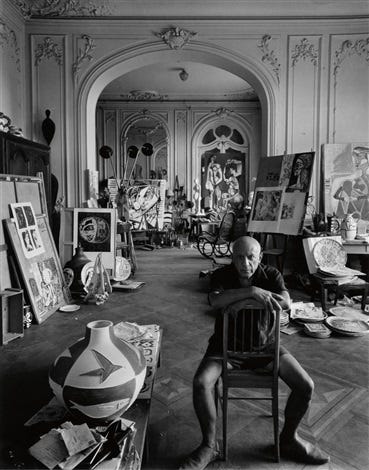

Another flashback: I’m sitting on the floor of the living room in our modest home in New Jersey, gazing in awe at a book of photographs. Maybe I’m 10 years old. It’s not the first time I’ve lingered with this book, a gift from a French exchange student who stayed with us one summer. We didn’t have many books in our home (“that’s what public libraries are for”) so it’s no surprise that I found this book so compelling. The photo essay portrays the artist, Pablo Picasso, in his grand home (Villa La Californie) on the coast of France. We see him in various palatial rooms, surrounded by his sculptures, paintings and ceramics, feasting with friends, and strolling down the beach with a lover on his arm.

From The Private World of Pablo Picasso, a photo essay by David Douglas Duncan, 1958

The images in this book became embedded in my imagination. His version of success, a gorgeous place to work, with beautiful friends, lovers, children, and animals, wonderful food, beaches to wander, and all kinds of art absolutely everywhere became a touchstone for me. As I got to know his work better, I fell in love with his drawings; the bold and expressive marks felt so freeing, and his imagery pointed towards a world of liberation from bourgeois mores. That he was a political radical engaged in the progressive movements of the time, and painting fierce works about injustices, made the world he lived in that much more appealing. While the fantasies that these photos conjured up remained a fixation for quite some time, they wilted quite a bit once I learned of Picasso’s misogyny. Add to that, more understanding of how the art market functions, and the allure of his world dissipated almost entirely.

Exposure to different value systems, far away from conventional pathways shifted my aspirations. At age 15, I was invited by a classmate, to join a local Unitarian youth group. It was my first encounter with a spiritual or religious group, and I remember my parents cautioning me to stay away from the church (they were so religion-phobic). At my very first meeting, I was invited into a series of “sensitivity training” exercises developed by the “human potential movement” to help us relate to each other more deeply. Although I was initially quite shy, I was also delighted to find a group of peers who wanted to work on themselves and change the world. A friendship that emerged from that group introduced me to yoga, vegetarianism, the poetry of Allen Ginsburg, the Blues, marijuana, LSD and other psychedelics, hitchhiking, bushwhacking into the source of the Hudson River, listening to the wise words of Krishnamurti, Helen and Scott Nearing, “Love-In’s” in Central Park, and just about every other thread of the counterculture’s crazy quilt. We went to anti-war marches together and conjured up visions of the world we wanted to live in. Guided by the music of that time (I’m hearing some Jefferson Airplane in my head right now) I willingly leaped into the collective swelling of change. I went to a college far away from the snooty East Coast Ivy League aura, at a school where I thought I could find friends with whom I could build an alternative universe and escape the rat race.

When my parents decided to take me on a tour of colleges that they thought I should go to (private, elite schools in New England that they never could have afforded), I already knew that I was going to be rejecting the visions that my parents (particularly my mom) had for me. She meant well. Over the years, I’ve developed deep compassion for my mom’s journey in the world. On top of carrying epigenetic trauma of displacement and persecution carried by her parents and our ancestors, she was never able to shed the damage caused by the deprivations of her own childhood. She grew up sharing a bed with two sisters and an aunt. It was the Depression and she was tasked with caring for the three younger siblings while both parents worked in the grocery store downstairs. The blacklisting of my dad also dramatically altered their lives. He was an anti-fascist scientist and the McCarthy Period was punishing for them. Living through periods of extreme scarcity, she had a lot weighing on my material success in the world, and my choices baffled and worried her deeply.

Carleton College was not known to my Northeast-centric parents or their friends, so they could not brag about my acceptance there. Although I had dreamed of going to UC Berkeley to participate in the great, fermenting culture of social change that seemed so visible there, a more gentle act of rebellion was to choose this not so prestigious college in the Midwest. Carleton was not without its own pretensions and elitism, but I was mostly blind to those factors while I was there. I was there for the intellectual, political, and cultural community, and to find comrades for the journey. Only in retrospect can I see how the culture of the school groomed all the students for a certain kind of success. I was supposed to become a “professional” after I graduated, get a master’s degree or become an entrepreneur of some sort. Even if one was committed to being a grass roots activist or a bohemian, the economics of the 1980s real estate market made it hard for anyone to get by on a part-time job, so many of my peers had to ratchet down their visions unless they were born to or married into wealth.

Ironically, just before I graduated from college, one of my closest friends, an art history major, told me that if I didn’t go to NYC and test myself there, I would always regret it. I was of two minds; I had been dreaming of forming or joining a kibbutz-like collective. I had lived on two of those in Israel, and had been invited to join one, but I could not fathom living in an apartheid-structured country, militarized and violent; and it has only grown more so since I lived there in 1972. The steps to find and create a rural or urban collective seemed daunting to me, more daunting than proving my value in my parents’ hometown, NYC, so I decided to trust my friend’s advice. First I would untangle the mysteries of being a NY artist, find a cohort to collaborate with, develop a more finely tuned understanding of the political moment, and develop my artistic voice, then later I might find allies to create an ecotopic experiment.

Given that my mom was deeply disappointed with my choice to be an art major in college, it is no surprise that she implored me to apply to law or business school once she saw the cockroach-ridden tenement apartment I was sharing in the East Village. I told her that she had no concept of who I was or wanted to be. I was more or less happily working three part-time jobs, hanging out and sharing food with a motley crew of baby poets, artists, healers and activists, while creating paintings and drawings on the floor of my bedroom (that was also the living room).

I did concede a little to my mother’s insistence on finding a pragmatic path for my artistic gifts. Through a relative, she was successful at getting me an interview with an art director at a major record company. I brought him slides of my portfolio of paintings, and after looking at them, he said, “well, you’re a fine artist and you should just keep doing that, but if you want to try your hands at a jazz or classical album cover, we will give you a chance, and if we don’t like what you do, we’ll pay you a kill fee.” He offered me a lot of money just to fail, but walking through the Madison Avenue offices turned my stomach. I intuitively knew this was the wrong context for me. The culture there felt creepy and superficial, and I never called him back. Dozens of years later, I told this story in lecture hall of over a hundred graduating art majors at CSULB who were taking my course, Issues in the Arts, and I could hear a palpable groan move through the room. It was hard for them to fathom why someone would turn down an opportunity like that for instinctive or ethical reasons. Many of them were already quite cynical and assumed that it would be impossible to make a living without huge compromises. Others were coming from extreme hardship, and knew that they could never turn down an offer like the one he’d made. I didn’t like the smell of nepotism that brought me into his office. I wanted to walk through doors because they were doors I wanted to go through and aligned with my values. Aside from that, at the time, I had the privilege of low rent, sufficient income, and was hoping to get into grad school so that I could teach.

More about my grad school years and entering the NYC art world in Part 2….and what are possible ways to decolonize ourselves from the old paradigms of success….

This confirms why I have always felt a kinship and viewed you as a Conrad and a Shero. You have had the tenacity to go beyond what most creative humans can withstand, and it is so honorable. Thanks for putting these words down. They provided me with a needed realignment on a day when I wondered if I'm just crazy and alone in this life.